A walk around my writer’s block

It took me thirty years to get from wanting to write a novel to finishing one. I walked away from writing several times, but I always came back, because deep down I knew it was a vital part of who I imagined myself to be.

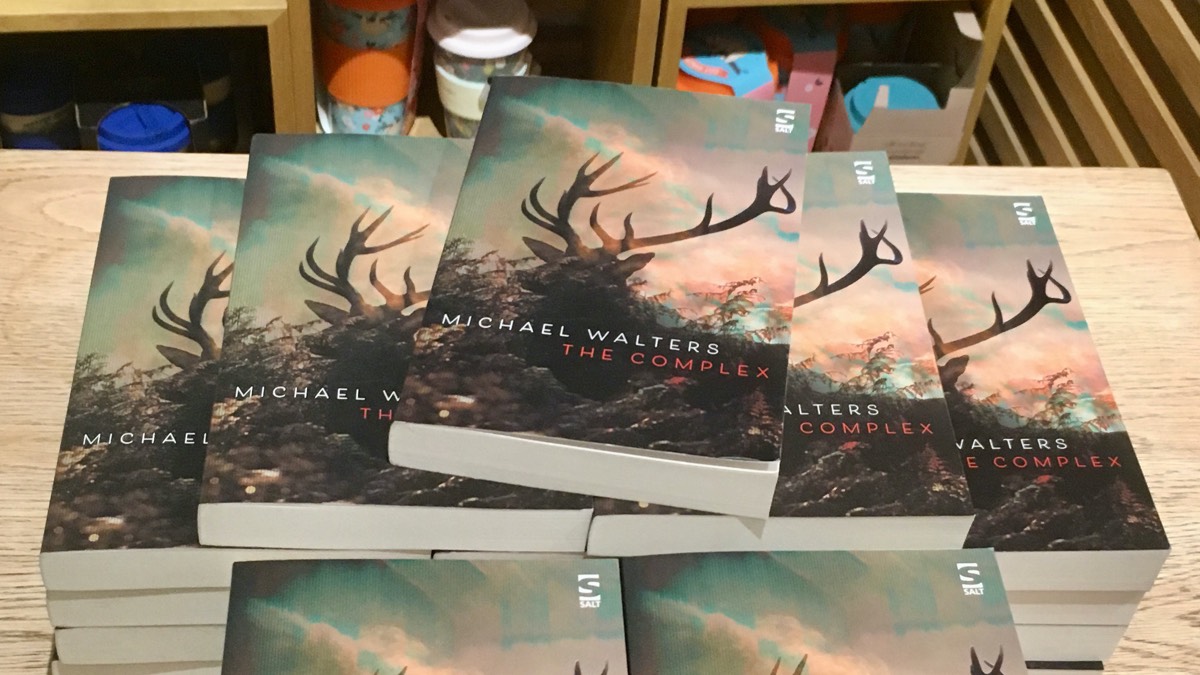

My debut novel, The Complex, came out in August 2019, and while I feel lucky and tremendously grateful it got out into the world, it already feels like it is being washed away by the endless river of words that is literary culture. I keep playing the publishing timeline game — a year to write a draft (The Complex took three), six months to edit (ha, in my dreams), another six months to get it picked up by a publisher (I wish), who will probably want changes (the bastards), and six more months to go through the publishing pipeline (it never happens this fast). That’s two-and-a-half years, with excellent weather, a reliable map, and no mishaps. Let’s say three (lol).

But there is something about writer’s block I need to explore first. I’ve spent most of my writing life feeling blocked in one way or another and I want to know more, perhaps so that I can avoid them when writing my next novel.

Let’s take a stroll around my psychic neighbourhood.

Teenage dirtbag

When I was sixteen, I had three dreams of what I wanted to do with my life: professional tennis player, astronaut and writer.

Nobody had told me these things were impossible, or even particularly unlikely, although I was beginning to suspect that I wasn’t going to win Wimbledon. This was 1989, in Port Talbot, South Wales, and I had to choose my A-level subjects. The college couldn’t handle students doing Physics and English simultaneously, so I had to choose: astronaut or writer?

I had a handful of astronomy books, with illustrations of planets, stars and black holes, and I often looked at them before I went to sleep. Space was a safe place for me, far away from family arguments and the daily shames of teenage life. I didn’t write, but I liked Dungeons and Dragons, and I spent hours drawing intricate worlds on graph paper.

I also loved to read. My father was an electrician in the steelworks. His shifts were long and varied — he could be on mornings, days, nights or doing overtime — and when he was home he would lose himself completely in books. You could call his name from six feet away, and he wouldn’t hear you. Once a month he would get the latest bestseller delivered through his book club, and I would beg him to hurry up reading them, so I could go next — Stephen King, James Herbert, Stephen Donaldson, Dean Koontz, all the big eighties’ horror, fantasy and thriller writers. My mother liked crime novels, but I wanted gore, scares and other worlds.

My stutter started when I was ten years old. It was like words were stuck in my chest, breathing became harder, and it made me feel panicky — like I was drowning in the words I couldn’t say. Seeing people’s faces as I stuttered made it worse, because they couldn’t help, and then I was drowning both of us, so I avoided eye contact. When every interaction is like that, the rational thing to do is to avoid interactions as much as possible. It was so severe when I was sixteen that I could hardly speak to anyone outside my closest circle of family and friends. Answering the telephone was terrifying. Asking for something in a shop was a torment. Talking to women I found even slightly attractive was completely impossible.

Faced with an A-level choice between cool, rational science (with boys), or warm, emotional literature (with girls), and knowing in English I would have to read aloud in class, it wasn’t a choice at all. I took Physics, Maths and Chemistry. Two years later, in 1991, I became the first person in my family to go to university, and to everyone’s surprise except me, I went as far away from home as I could, to the University of Kent, Canterbury, to study Physics with Astrophysics.

My world opened up. Lift off.

Science and literature

I was an average student, and while I loved the astrophysics part, my maths wasn’t strong. In the second year I had an emotionally catastrophic relationship, and I fell a long way behind. After that, I didn’t know how to ask for help, so I stumbled from term to term, enjoying myself socially, but struggling academically.

I left it too late to recover. That’s how I found myself in the university library, a few weeks before my finals, staring at my sparse study notes, realising that there was a chance I might not just do badly, but fail my entire degree. It hit me hard, just like that, in a moment. Stunned, I remember walking blindly around campus, before returning to the library, where through some unconscious longing I ended up in American Literature. I spotted Catcher in the Rye and pulled it out. My comprehensive school English teacher had once given it to me to read. Nearby was For Whom the Bell Tolls. Apt. I’d read that too, and I remembered the romance of it, as well as the clarity of the language. Being amongst those books calmed me. So, I took them out.

My friends thought I’d lost the plot when they saw me reading Ernest Hemingway weeks before final exams. They didn’t understand that it was part of me letting go of my dream. I had twigged that I wasn’t going to be an astronaut, or an astronomer, or even get on the MSc in Medical Physics I’d looked at. I kept studying, but I knew I was just trying to get through it. Somehow I scraped a third. I moved back to my parents’ house. All my friends were talking about graduate jobs, but I couldn’t get one. I applied for, and was rejected from, over fifty jobs that summer. That’s how I fell into administrative work.

Last dream standing

Becoming a writer was the only dream I had left, but I also needed money, so I mashed them together and decided to become a journalist. I did some voluntary work on a local paper, then borrowed four grand to do the formal training, and landed a job on the Salford Advertiser, Manchester. I lasted six weeks. The salary was tiny, Manchester was expensive, my job required a car that I couldn’t afford, I didn’t know anybody, I was in debt, and I hadn’t clocked just how combative the job of a reporter in a city could be. After a couple of weeks, my stutter started to come back, and by the end I was hiding in the toilets for half an hour at a time, afraid to go back to my desk. I was done.

It took months to recover. That summer, in 1996, I found a new administrative job, this time in Mumbles, Swansea, and I began to slowly pay back my debt. My mother gave me an old typewriter, so I could try writing short stories. There were no local writing groups, or evening classes, or support networks. I had no readers and no feedback. It was a lonely business. I kept going for two years, but writing wasn’t a pleasure; it was a war of attrition between my ambition and a harsh social, economic and cultural reality.

I’ve always thought of this period as my first experience of writer’s block. I was desperate to somehow make writing work, but I was completely disconnected from the writing and publishing world. Looking back, I don’t think it was writer’s block. I was just in the wrong place, at the wrong time, without any access to learning resources.

Exhausted, I stopped writing, and in 1998, just as I finished paying off my journalism loan, I quit my admin job and took out a new loan, this time to study computing. I began a one-year MSc Computer Science conversion course at University of Wales, Swansea, and started my life as a software developer.

Duty, love and staying sane

In the following years I had several coding jobs, got married, had a baby and bought a house.

In 2004, seemingly from nowhere, I blasted out the first draft of a novel. I was dissatisfied with my job, having a two-year-old was hard, and I needed to feel creative — I remember it as a thrilling three-month frenzy, followed by another six months of soul-shredding frustration. I couldn’t make the ending work. Eventually, I had to stop. By the end of 2004, I was at a really low ebb, and I was lucky I had the money and will to be able to find a good psychotherapist. I questioned everything. It seemed like all of my childhood dreams were dead, and it hit me that I was into my thirties, and I still didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life.

I’d written the first draft of a novel — success! — but I knew it wasn’t good, and I didn’t know why. This block was a lack of skill, not a psychological block. With the help of a mental health professional, I managed to tack from quite dangerous waters into one of the most creatively interesting periods of my life.

I began to look for alternatives to writing. I did three counselling certificates, one after another. I took singing lessons. I bought a guitar. I tried to learn the piano. I volunteered with the Samaritans. My son was getting older, my job was stable, and life became easier. In 2007, I allowed myself to think about writing again. I found an online creative writing module with the Open University and, over the next three years, I learned how to write short stories, poems, plays and essays, and I left with a Certificate in Creative Writing.

In 2009 we had another baby and moved house. I had a new job with a much longer commute. Without the structure and deadlines of a course, I stopped writing new material. I still wrote in my notebooks, but I wrote about process, the nature of creativity, psychology and psychotherapy, and why I wasn’t writing. I wrote about my health. I wrote about my health a lot.

I returned to psychoanalytic psychotherapy at the end of 2010. It felt like I had unfinished business. I was desperately trying to write a novel, but life was busy, and psychotherapy was a big creative undertaking in itself. Psychotherapy was fruitful, but often excruciating, and I stopped writing fiction completely, concentrating instead on my dreams, memories, and patterns of thought and feeling.

I felt blocked, but again, in retrospect, it wasn’t writer’s block. I had chosen therapy over writing, but I fought against that choice all the way. However, psychotherapy taught me how to use my intuition and how to listen to messages coming from my unconscious mind. These are priceless weapons in a writer’s armoury.

A breakthrough in my writing efforts came when I discovered Twitter. Once I got to grips with the mixture of anonymity and instant feedback, I started to really play with improvised writing. It was a potent tool alongside psychotherapy. I already knew how I tended to censor my thoughts and feelings, and Twitter gave me a way to write in public without inhibition.

The downside to Twitter was the ease with which I projected aspects of myself onto strangers, so it became perilously emotionally involving, and the many tweets I put into the world gave me nothing tangible in return. Likes and retweets didn’t get me closer to my dream. I needed to change tack if I wanted to write a novel.

The intuitive craft

I decided to stop psychotherapy and in 2014 I applied to study an online MA in Creative Writing at Manchester Metropolitan University. The application required a recent 2000-word story. By this point I had written thousands of tweets, but hadn’t written a short story in over five years.

I took my time. For the first couple of weeks I just wrote in my notebook about what I was trying to do, how I felt and how I might go about it. I was getting my unconscious engaged with the problem. I started having vivid dreams, and I wrote them down, just as I had learned to do in psychotherapy. I read my old textbooks and notebooks. I researched the MA reading lists. I deactivated my Twitter account. It was intense, sometimes unpleasantly so, and tiring.

Around the third week, a line of dialogue popped into my head, followed by a reply. I wrote them down. Then came a few lines of description. A name. A memory. I wrote 300 words. The next day I wrote another 300 words with the same character. It felt good. I took four weeks, but I finished the story, and a month after that MMU accepted my application.

Why didn’t I experience the writer’s block I seemed to have? I think it was because I had a deadline, a word count, and crucially, both skills and a very strong reason. THe story was going to be read and something would happen as a result — it wasn’t going to sit on a slush pile for months, or be lost in thousands of competition entries. I was writing a story to show I was good enough for a course that I hoped would change my life.

It did change my life. It would be three years before I finished my first attempt at The Complex, and another year until it was good enough to be published by Salt. My tutor, Nicholas Royle, was endlessly encouraging and enthusiastic about my work, and his belief in me helped me believe in myself.

A life’s work

Words have always been a struggle for me. I can see more clearly now what was blocking me from writing at different points in my life. Writer’s block is a specific thing — you can’t have writer’s block if you don’t already have writing craft. My story is one of a man hitting a series of obstacles that he had to surmount.

I am not at all a perfectionist in most things, but in writing I am. I’ve worked my whole life to be able to express myself clearly, in speech and the written word. I’ve always known when the words weren’t right. That can be debilitating, especially if you are solving a complex writing problem for the first time, and a literary novel is a seriously complex writing problem, because for almost the entire process, the words are not right.

I find writing painful. No wonder it’s hard to start writing something new. But I have learnt some things that help.

The first thing is, I’m better at recognising when I’m procrastinating because I’m afraid. I can listen to that fear, and we can reach an agreement. I’ve also learned to trust my writing process, although I still have to remind myself what that is, because it’s slightly different every time. I do know that once I start, I’ll be okay. That makes it easier to start.

Secondly, my confidence in my ability to write something good is much higher now, which helps me get going. This has come from the support of wonderful teachers, like Nicky Harlow at the Open University, and Nicholas Royle at MMU. There is nothing like the enthusiasm and belief of people you trust and respect. That’s what I was missing in my twenties. Teachers.

And finally, I believe in myself as a writer now, but I know self-belief is intangible. Our demons are personal. For me, writer’s block is an emotional block, like my stutter was. It’s a kind of overwhelm, where my mental circuits get fried because they are overloaded. The answer is almost always to slow everything right down and to pay quiet attention to what’s going on under the surface of my mind, to stop caring so much that I rush. I try to let things take their own sweet time.

Onwards

That feels like the end of our stroll together. I hope there was something useful in here for you. I’m currently meandering in the foothills of my next novel. It has a title. It has locations. It has some characters, albeit fuzzy ones. There are no words written yet. I just need a line of dialogue. Perhaps it’s time to start.