Michael Walters

Notes from the peninsula

In the foothills

Graham Swift once said, ‘All novelists must form personal pacts with the pace of their craft.’ Now I am deep in the foothills of my second novel, that quote is a comfort, because I’d forgotten how hard it is to write fifty thousand words. (I plucked fifty thousand from the air because it feels less intimidating than eighty thousand, but of course I have no idea how long the story will end up being. So much of it is mind games. I could equally think of it is ten five-thousand-word short stories that share characters and work as a cohesive whole, but that sounds immeasurably harder.)

The pace of my craft is not as fast as my ego would like. It’s a slow journey, with many meandering paths — all necessary. I know at a rational level getting frustrated is counterproductive, but I can’t help it. Donna Tartt describes a wrong turn while writing The Goldfinch (3:50) that was eight months of work, but it gave her information she couldn’t have found out any other way. If this bit isn’t fun, you know, the writing bit, what’s the point of writing at all?

In a summer holiday spurt, I wrote just over ten thousand words. The autumn stretches ahead, with more COVID-19, the American election (which shouldn’t be my business, but is), and Brexit, all looming in my imagination. I am safe, and my family is well, for which I am grateful. I know how lucky I am. But the technology that makes working from home possible and gives me a degree of financial security, is also the source of all distractions. I must close my ears to that noise. Those ten thousand words want to become twenty thousand. I can hear them whispering. They are the signal.

If I am in the foothills of a novel, the ascent to the summit comes from following the paths marked with the golden thread. In the land of the imagination, intuition is queen. Connections are as common as spiders webs. You don’t see golden threads or spiders webs when you rush.

Hm. I didn’t see that fairy tale turn coming. So, on we go. What did the grandma say? Keep to the path.

31 Days of Horror, 2020

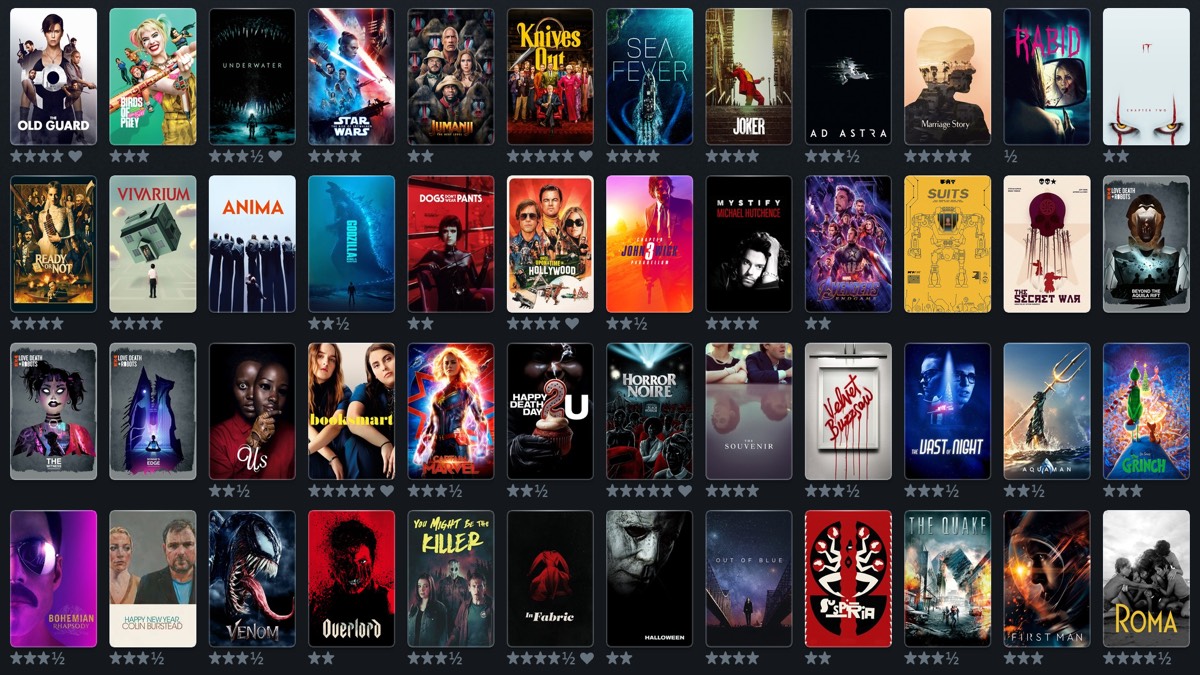

With 2020 being a demented shitshow, I did fleetingly wonder if I wanted to do #31DaysOfHorror again this year, but then I remembered why I love horror films — they are an escape from reality; they are an outlet for the darkness in me; and they are smart, subversive and funny, as well as gnarly, gruesome and grim. I find them endlessly fascinating, invigorating and fun.

Now #31DaysOfHorror might seem extreme (the original idea was you watch a horror film every day in October, culminating in Halloween, and post your pick each day with the hashtag), and in my first attempt, in 2018, I was such a purist about it, it really did feel extreme. It was actually bad for my mental health. I watched a horror film every day, apart from, ironically, the very last day, Halloween, when I was so emotionally exhausted I completely forgot to do it. My unconscious mind just said no.

But I did watch a lot of films I’d meant to watch for years. There was a lot of fun to be had if I could better pace myself. In 2019, I did it again, this time remembering that horror films vary enormously, and seasoning the stronger fayre with a dash of comedy or sci-fi, which improved the whole experience. I also added the ‘five picks from September’ rule, for days when watching a horror film was a bad idea. That was a good compromise between making it a challenge and looking after myself.

For 2020, I want to go a step further. My plan is to write a short blog post about each film, just a couple of paragraphs to help me process my thoughts, that I can link to instead of the Letterboxd page. Perhaps it will send a few more people to my website and raise awareness of The Complex.

Sadly, I deleted my 2018 Twitter list, but thanks to the magic of Letterboxd, here are both lists for the record.

2019 — 31 Days of Horror

- The Eyes of Laura Mars (1978)

- Ringu (1998)

- A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night (2014)

- Don’t Look Now (1973)

- The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)

- Possession (1981)

- Troll Hunter (2010)

- Rabid (1977)

- Jurassic Park (1993)

- Drag Me to Hell (2009)

- Sunshine (2007)

- Count Yorga, Vampire (1970)

- Friday the 13th (1980)

- Carrie (1976)

- A Nightmare on Elm Street Part 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985)

- It Chapter Two (2019)

- 28 Weeks Later (2007)

- A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987)

- The Day of the Triffids (1962)

- Anaconda (1997)

- Black Sunday (1960)

- Dead of Night (1945)

- Rec (2007)

- From Beyond (1986)

- The Final Girls (2015)

- Se7en (1995)

- Alien (1979)

- Prometheus (2012)

- Alien: Covenant (2017)

- Trick ’r Treat (2007)

- Joker (2019)

2018 — 31 (cough, 30) Days of Horror

- Predator (1987)

- Hellraiser (1987)

- Halloween H20: 20 Years Later (1998)

- Scream 2 (1997)

- Scream 3 (2000)

- Night of the Demon (1957)

- Cat People (1982)

- Pontypool (2008)

- The Borderlands (2013)

- The Birds (1963)

- Deep Red (1975)

- Season of the Witch (1972)

- A Dark Song (2016)

- Dawn of the Dead (1978)

- Under the Skin (2013)

- American Psycho (2000)

- Repulsion (1965)

- The Company of Wolves (1984)

- It (2017)

- Venom (2018)

- The Evil Dead (1981)

- Suspiria (1977)

- mother! (2017)

- The Fly (1986)

- Poltergeist (1982)

- Jennifer’s Body (2009)

- Night of the Living Dead (1968)

- The Lost Boys (1987)

- Cat People (1942)

- Urban Legend (1998)

- Damn you, unconscious mind! shakes fist

The inner Wonder Woman

Last night, I had a deep dream of stasis and being held. I seemed to accept it, though there was a suggestion of pressing against constraints. I can’t remember any details. It’s a feeling from a fragment.

Yesterday, I read an article about the making of Wonder Woman 1984, and it reminded me of a film I’ve been meaning to see, Professor Marston and the Wonder Women. Professor William Marston created Wonder Woman, but also, with his wife Elizabeth Marston, an early prototype of the lie detector — or, hilariously, the Lasso of Truth.

One of William Marston’s beliefs was that men’s destructive egos benefited from submission to a powerful, benevolent woman. That power dynamic feels connected to what we are being asked to do during this pandemic. Perhaps my dream comes from feeling unconsciously that I am being asked to submit to a set of rules, a constriction of my freedoms, for good reason, and while the constraints might chaff a little, I’m fundamentally okay with that for now.

I loved Lynda Carter’s Wonder Woman, who was a staple of my early childhood on TV, along with Man From Atlantis and The Six Million Dollar Man. These were the dramatic personae of my five-year-old Saturday evenings, while my father was still at work, and my mother made dinner. As I submitted to the television, with its potent, dangerous characters, and as I submitted to my mother’s unknowable timetable, juggling the adult tasks of a busy household, so I submit now to the instruction to stay home.

There can be pleasures within constraints. Articles on creative writing are always talking about restricting yourself as a way of freeing up your imagination. But in this case, with all the terrible things happening in the world, it mostly feels like trying to make the best of a bad situation. There are worse ways of coping with confinement than linking it to childhood comforts.

My favourite five books of 2019

In 2019, on Goodreads, I set myself the challenge of reading 52 books. I succeeded — I wanted to read more, and the challenge did the trick. There were periods where I hardly read at all, and to stay on track I found myself choosing shorter books. I read ten books in November and December, so while I had fallen a little behind, I was pretty consistent all year.

My favourite five books of 2019:

- The Comfort of Strangers, Ian McEwan (1981)

- You Were Never Really Here, Jonathan Ames (2013)

- In the Cut, Susanna Moore (1995)

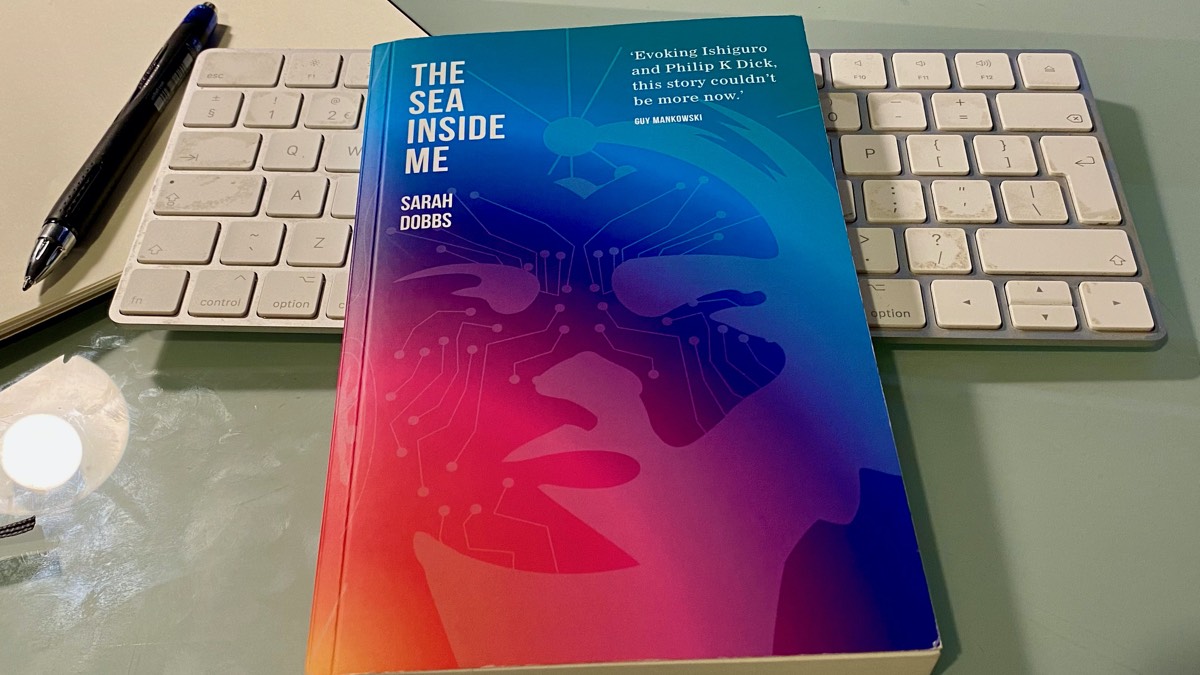

- The Sea Inside Me, Sarah Dobbs (2019)

- My Name is Lucy Barton, Elizabeth Strout (2016)

I’m reading less in 2020, and even my more relaxed target of 35 books is feeling a little too much. I didn’t help myself by picking The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Tales, by HP Lovecraft, and then getting stuck in his prose stodge.

Alice’s Masque, by Lindsay Clarke, is the book I’m reading right now. I picked it up from a secondhand book shop years ago and never got around to it. It’s good. I’m a third of the way in. I don’t know where he’s taking me, but he’s earned my trust. I’m hopeful it’ll be on my 2020 list. Time will tell.

A walk around my writer’s block

It took me thirty years to get from wanting to write a novel to finishing one. I walked away from writing several times, but I always came back, because deep down I knew it was a vital part of who I imagined myself to be.

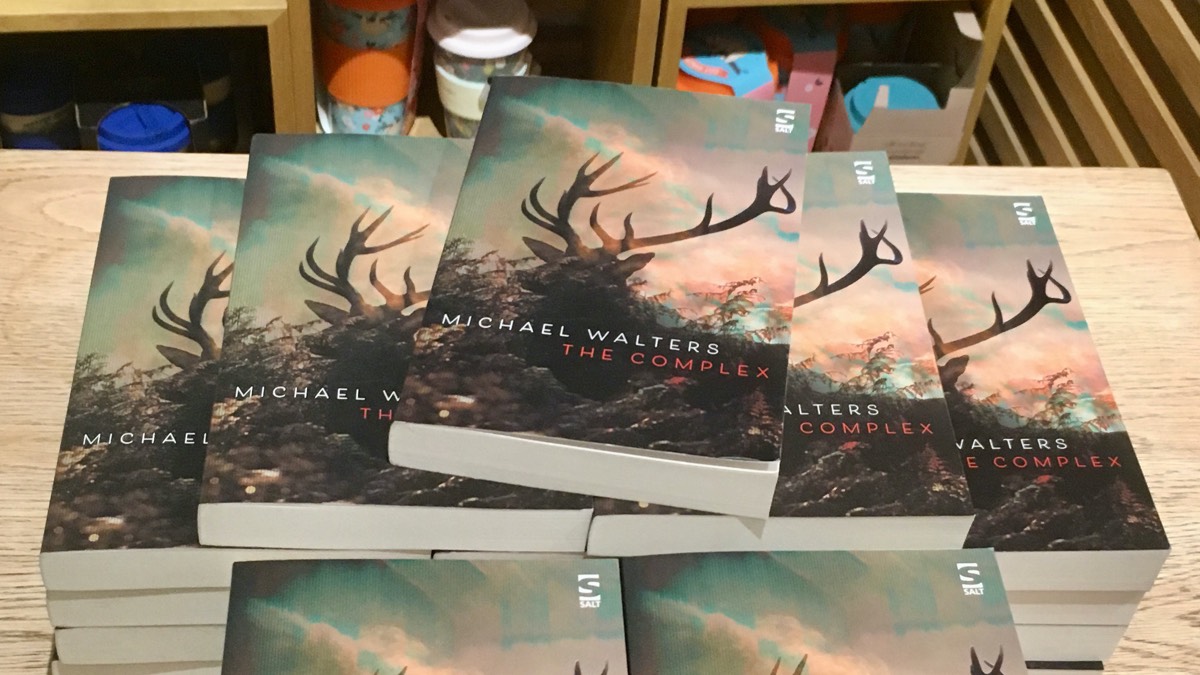

My debut novel, The Complex, came out in August 2019, and while I feel lucky and tremendously grateful it got out into the world, it already feels like it is being washed away by the endless river of words that is literary culture. I keep playing the publishing timeline game — a year to write a draft (The Complex took three), six months to edit (ha, in my dreams), another six months to get it picked up by a publisher (I wish), who will probably want changes (the bastards), and six more months to go through the publishing pipeline (it never happens this fast). That’s two-and-a-half years, with excellent weather, a reliable map, and no mishaps. Let’s say three (lol).

But there is something about writer’s block I need to explore first. I’ve spent most of my writing life feeling blocked in one way or another and I want to know more, perhaps so that I can avoid them when writing my next novel.

Let’s take a stroll around my psychic neighbourhood.

Teenage dirtbag

When I was sixteen, I had three dreams of what I wanted to do with my life: professional tennis player, astronaut and writer.

Nobody had told me these things were impossible, or even particularly unlikely, although I was beginning to suspect that I wasn’t going to win Wimbledon. This was 1989, in Port Talbot, South Wales, and I had to choose my A-level subjects. The college couldn’t handle students doing Physics and English simultaneously, so I had to choose: astronaut or writer?

I had a handful of astronomy books, with illustrations of planets, stars and black holes, and I often looked at them before I went to sleep. Space was a safe place for me, far away from family arguments and the daily shames of teenage life. I didn’t write, but I liked Dungeons and Dragons, and I spent hours drawing intricate worlds on graph paper.

I also loved to read. My father was an electrician in the steelworks. His shifts were long and varied — he could be on mornings, days, nights or doing overtime — and when he was home he would lose himself completely in books. You could call his name from six feet away, and he wouldn’t hear you. Once a month he would get the latest bestseller delivered through his book club, and I would beg him to hurry up reading them, so I could go next — Stephen King, James Herbert, Stephen Donaldson, Dean Koontz, all the big eighties’ horror, fantasy and thriller writers. My mother liked crime novels, but I wanted gore, scares and other worlds.

My stutter started when I was ten years old. It was like words were stuck in my chest, breathing became harder, and it made me feel panicky — like I was drowning in the words I couldn’t say. Seeing people’s faces as I stuttered made it worse, because they couldn’t help, and then I was drowning both of us, so I avoided eye contact. When every interaction is like that, the rational thing to do is to avoid interactions as much as possible. It was so severe when I was sixteen that I could hardly speak to anyone outside my closest circle of family and friends. Answering the telephone was terrifying. Asking for something in a shop was a torment. Talking to women I found even slightly attractive was completely impossible.

Faced with an A-level choice between cool, rational science (with boys), or warm, emotional literature (with girls), and knowing in English I would have to read aloud in class, it wasn’t a choice at all. I took Physics, Maths and Chemistry. Two years later, in 1991, I became the first person in my family to go to university, and to everyone’s surprise except me, I went as far away from home as I could, to the University of Kent, Canterbury, to study Physics with Astrophysics.

My world opened up. Lift off.

Science and literature

I was an average student, and while I loved the astrophysics part, my maths wasn’t strong. In the second year I had an emotionally catastrophic relationship, and I fell a long way behind. After that, I didn’t know how to ask for help, so I stumbled from term to term, enjoying myself socially, but struggling academically.

I left it too late to recover. That’s how I found myself in the university library, a few weeks before my finals, staring at my sparse study notes, realising that there was a chance I might not just do badly, but fail my entire degree. It hit me hard, just like that, in a moment. Stunned, I remember walking blindly around campus, before returning to the library, where through some unconscious longing I ended up in American Literature. I spotted Catcher in the Rye and pulled it out. My comprehensive school English teacher had once given it to me to read. Nearby was For Whom the Bell Tolls. Apt. I’d read that too, and I remembered the romance of it, as well as the clarity of the language. Being amongst those books calmed me. So, I took them out.

My friends thought I’d lost the plot when they saw me reading Ernest Hemingway weeks before final exams. They didn’t understand that it was part of me letting go of my dream. I had twigged that I wasn’t going to be an astronaut, or an astronomer, or even get on the MSc in Medical Physics I’d looked at. I kept studying, but I knew I was just trying to get through it. Somehow I scraped a third. I moved back to my parents’ house. All my friends were talking about graduate jobs, but I couldn’t get one. I applied for, and was rejected from, over fifty jobs that summer. That’s how I fell into administrative work.

Last dream standing

Becoming a writer was the only dream I had left, but I also needed money, so I mashed them together and decided to become a journalist. I did some voluntary work on a local paper, then borrowed four grand to do the formal training, and landed a job on the Salford Advertiser, Manchester. I lasted six weeks. The salary was tiny, Manchester was expensive, my job required a car that I couldn’t afford, I didn’t know anybody, I was in debt, and I hadn’t clocked just how combative the job of a reporter in a city could be. After a couple of weeks, my stutter started to come back, and by the end I was hiding in the toilets for half an hour at a time, afraid to go back to my desk. I was done.

It took months to recover. That summer, in 1996, I found a new administrative job, this time in Mumbles, Swansea, and I began to slowly pay back my debt. My mother gave me an old typewriter, so I could try writing short stories. There were no local writing groups, or evening classes, or support networks. I had no readers and no feedback. It was a lonely business. I kept going for two years, but writing wasn’t a pleasure; it was a war of attrition between my ambition and a harsh social, economic and cultural reality.

I’ve always thought of this period as my first experience of writer’s block. I was desperate to somehow make writing work, but I was completely disconnected from the writing and publishing world. Looking back, I don’t think it was writer’s block. I was just in the wrong place, at the wrong time, without any access to learning resources.

Exhausted, I stopped writing, and in 1998, just as I finished paying off my journalism loan, I quit my admin job and took out a new loan, this time to study computing. I began a one-year MSc Computer Science conversion course at University of Wales, Swansea, and started my life as a software developer.

Duty, love and staying sane

In the following years I had several coding jobs, got married, had a baby and bought a house.

In 2004, seemingly from nowhere, I blasted out the first draft of a novel. I was dissatisfied with my job, having a two-year-old was hard, and I needed to feel creative — I remember it as a thrilling three-month frenzy, followed by another six months of soul-shredding frustration. I couldn’t make the ending work. Eventually, I had to stop. By the end of 2004, I was at a really low ebb, and I was lucky I had the money and will to be able to find a good psychotherapist. I questioned everything. It seemed like all of my childhood dreams were dead, and it hit me that I was into my thirties, and I still didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life.

I’d written the first draft of a novel — success! — but I knew it wasn’t good, and I didn’t know why. This block was a lack of skill, not a psychological block. With the help of a mental health professional, I managed to tack from quite dangerous waters into one of the most creatively interesting periods of my life.

I began to look for alternatives to writing. I did three counselling certificates, one after another. I took singing lessons. I bought a guitar. I tried to learn the piano. I volunteered with the Samaritans. My son was getting older, my job was stable, and life became easier. In 2007, I allowed myself to think about writing again. I found an online creative writing module with the Open University and, over the next three years, I learned how to write short stories, poems, plays and essays, and I left with a Certificate in Creative Writing.

In 2009 we had another baby and moved house. I had a new job with a much longer commute. Without the structure and deadlines of a course, I stopped writing new material. I still wrote in my notebooks, but I wrote about process, the nature of creativity, psychology and psychotherapy, and why I wasn’t writing. I wrote about my health. I wrote about my health a lot.

I returned to psychoanalytic psychotherapy at the end of 2010. It felt like I had unfinished business. I was desperately trying to write a novel, but life was busy, and psychotherapy was a big creative undertaking in itself. Psychotherapy was fruitful, but often excruciating, and I stopped writing fiction completely, concentrating instead on my dreams, memories, and patterns of thought and feeling.

I felt blocked, but again, in retrospect, it wasn’t writer’s block. I had chosen therapy over writing, but I fought against that choice all the way. However, psychotherapy taught me how to use my intuition and how to listen to messages coming from my unconscious mind. These are priceless weapons in a writer’s armoury.

A breakthrough in my writing efforts came when I discovered Twitter. Once I got to grips with the mixture of anonymity and instant feedback, I started to really play with improvised writing. It was a potent tool alongside psychotherapy. I already knew how I tended to censor my thoughts and feelings, and Twitter gave me a way to write in public without inhibition.

The downside to Twitter was the ease with which I projected aspects of myself onto strangers, so it became perilously emotionally involving, and the many tweets I put into the world gave me nothing tangible in return. Likes and retweets didn’t get me closer to my dream. I needed to change tack if I wanted to write a novel.

The intuitive craft

I decided to stop psychotherapy and in 2014 I applied to study an online MA in Creative Writing at Manchester Metropolitan University. The application required a recent 2000-word story. By this point I had written thousands of tweets, but hadn’t written a short story in over five years.

I took my time. For the first couple of weeks I just wrote in my notebook about what I was trying to do, how I felt and how I might go about it. I was getting my unconscious engaged with the problem. I started having vivid dreams, and I wrote them down, just as I had learned to do in psychotherapy. I read my old textbooks and notebooks. I researched the MA reading lists. I deactivated my Twitter account. It was intense, sometimes unpleasantly so, and tiring.

Around the third week, a line of dialogue popped into my head, followed by a reply. I wrote them down. Then came a few lines of description. A name. A memory. I wrote 300 words. The next day I wrote another 300 words with the same character. It felt good. I took four weeks, but I finished the story, and a month after that MMU accepted my application.

Why didn’t I experience the writer’s block I seemed to have? I think it was because I had a deadline, a word count, and crucially, both skills and a very strong reason. THe story was going to be read and something would happen as a result — it wasn’t going to sit on a slush pile for months, or be lost in thousands of competition entries. I was writing a story to show I was good enough for a course that I hoped would change my life.

It did change my life. It would be three years before I finished my first attempt at The Complex, and another year until it was good enough to be published by Salt. My tutor, Nicholas Royle, was endlessly encouraging and enthusiastic about my work, and his belief in me helped me believe in myself.

A life’s work

Words have always been a struggle for me. I can see more clearly now what was blocking me from writing at different points in my life. Writer’s block is a specific thing — you can’t have writer’s block if you don’t already have writing craft. My story is one of a man hitting a series of obstacles that he had to surmount.

I am not at all a perfectionist in most things, but in writing I am. I’ve worked my whole life to be able to express myself clearly, in speech and the written word. I’ve always known when the words weren’t right. That can be debilitating, especially if you are solving a complex writing problem for the first time, and a literary novel is a seriously complex writing problem, because for almost the entire process, the words are not right.

I find writing painful. No wonder it’s hard to start writing something new. But I have learnt some things that help.

The first thing is, I’m better at recognising when I’m procrastinating because I’m afraid. I can listen to that fear, and we can reach an agreement. I’ve also learned to trust my writing process, although I still have to remind myself what that is, because it’s slightly different every time. I do know that once I start, I’ll be okay. That makes it easier to start.

Secondly, my confidence in my ability to write something good is much higher now, which helps me get going. This has come from the support of wonderful teachers, like Nicky Harlow at the Open University, and Nicholas Royle at MMU. There is nothing like the enthusiasm and belief of people you trust and respect. That’s what I was missing in my twenties. Teachers.

And finally, I believe in myself as a writer now, but I know self-belief is intangible. Our demons are personal. For me, writer’s block is an emotional block, like my stutter was. It’s a kind of overwhelm, where my mental circuits get fried because they are overloaded. The answer is almost always to slow everything right down and to pay quiet attention to what’s going on under the surface of my mind, to stop caring so much that I rush. I try to let things take their own sweet time.

Onwards

That feels like the end of our stroll together. I hope there was something useful in here for you. I’m currently meandering in the foothills of my next novel. It has a title. It has locations. It has some characters, albeit fuzzy ones. There are no words written yet. I just need a line of dialogue. Perhaps it’s time to start.

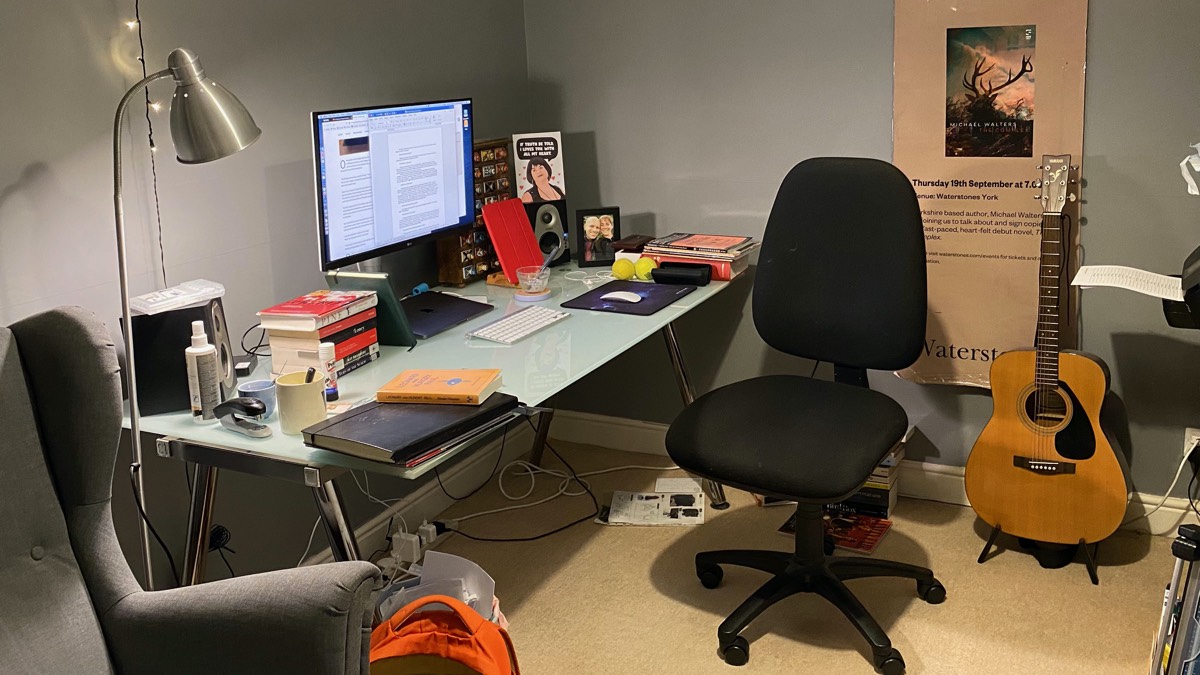

Escape room

I wrote a fun post about how I write and the room I write in, prompted by some great questions by Georgina Bruce. There are lots of others in her escape room series and I recommend them. She also has a short story collection out, This House of Wounds and a novella, Honeybones, with TTA Press.

This month I’ve spent an awful lot more time than usual in my escape room. The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed all of us back into our homes, and my writing room is now where I also do software development work for my employer. I returned to work full-time this month after several years using my Fridays to do the school run and be around in school holidays. I commute for three hours every day, so I arranged to work from home on Fridays. Well, now I’m working from home every day, as is my wife, and the children are home too.

I’m not complaining. I know how lucky we are. Now I need to figure out how to make the room I write in an escape room again.

First post, best post

I find it liberating to write whatever is next in my thoughts. The train doesn’t ever stop, not even for sleep, and for me, capturing some of that stream in a notebook bucket allows me to read those thoughts with some distance. With distance, I can make some sense out of it, and perhaps act with a little more forethought.

But writing for others is a different animal. When I know I’m going to share the thing I’m working on, I begin to notice less useful patterns — how I’ve mixed at least three different metaphors, for example. Of course that matters to the reader (because what sort of shitty writer does that? And brackets!), but for the purposes of making sense of myself to myself, it doesn’t matter at all. In fact it holds me back, because the stream is holy in a way grammar isn’t. (Don’t, as they say, @ me.)

I say all of this because I think it’s important to remember that, while I don’t think first thought is, as Allen Ginsberg used to say, best thought, it does have a unique value. First thought is pure intuition, and that might be right or wrong, but it is always truthful. Perhaps that does make it best thought. Hm.

I am not going to edit this. Well, no, I will edit it for spelling and grammar, but I’m going to leave the train of thought alone.

Minimalism

My son and daughter are both YouTube watchers, but until this year I’d never felt the need to try it. The whole influencers and cult of personality thing put me off. Then last week I decided to look on YouTube for tips on meditation and I found a Matt D’Avella video, I Meditated for 1 Hour Every Day for 30 Days.

D’Avella is a classic self-help vlogger who specialises in minimalist living and is a documentary filmmaker by trade, which makes his videos impeccably shot and edited. He’s personable, good-looking, self-aware, talks about his feelings, has a lovely apartment, and is funny. I watched the video, then watched all the others. He made me feel good. It was comforting.

I remember Leo Babauta’s Zen Habits blog from the late noughties (check out his archives, which go right back to January 2006), and in tech circles in particular, there was an endless debate about the best ways to live as simply and effectively as possible in an increasingly overwhelming online world. People were beginning to burn out — and this was way before social media became all-consuming. I was trying to start a business at the time, and I too bought Getting Things Done and The 4-Hour Workweek. I suppose I’m saying I have a mixed history with this stuff.

Minimalism, which is living simply and within your means, seems to be a hotter topic than ever. My wife and I have both worked four days a week for most of the last decade so that we can be around more for the children. In a way, minimalism is our natural philosophy, partly from financial necessity, but also because we both like order and neatness.

I develop software for a living, and I write stories in my spare time. Now that I’ve completed my Masters in Creative Writing, and The Complex has been published, I feel like I’ve levelled up to being a professional writer. I have two professions and I need to give them both their due. Fresh thinking is required.

So, to solve this complex problem, I did what I always do: I cleaned my desk.

I now have the piles of short story collections that were on either side of my monitor (and supporting my laptop speakers) on the shelves behind me. Novels live on the downstairs shelves, split between the living room and the kitchen-dining room. I can now do whatever I need to do on a sparsely populated desk without always thinking, I should really read one of those short story collections, or, I should roll those story dice for once and see what comes up, or, that tennis ball shouldn’t be there, but I don’t know where else to put it. (I put the tennis ball on the pile of useful things in the corner of the room that would usually be on my desk.)

So. I cleaned my desk. I feel like a minimalist. I have two professions. Got it. Onwards.

Writing and reviewing

I’m sitting in my kitchen listening to Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, and I have some thoughts about how it’s making me feel. Christine McVie is singing Songbird, a song she wrote, and while the lyrics are hopeful and full of love, her voice is delicate and sad.

This reminds me of a long-running debate I have with myself about whether it’s a good idea for me to write reviews. As a writer, I know how fragile the life of books can be, because they have to fight for attention, against all the stories and media and entertainment in the world, relying on scant marketing, rare good will and, if it’s lucky, word-of-mouth. A bad review can kill a book. Reviewers opinions are subjective. Some reviewers may hold more sway in the cultural landscape than others and some are more skilled readers than others. Tastes are different. We all have an opinion.

When I start making notes about what I like and don’t like about a book or film, since stories are what I care most about in that way, it’s not too many steps to a review that I could publish on my blog. Perhaps I could develop the skill enough to get a gig as a reviewer for a magazine or local newspaper. I have a book published now, that might count for something in the review marketplace.

This is where I catch myself thinking about what it would be like to get a bad review. I want books to find readers. Just because I hate a book, someone else might absolutely adore it. If I were a professional critic I don’t think this would bother me, because it’s self-evident that one person’s opinion is just that, and there’s an ocean of opinions out there. But being a writer myself, meeting other writers, willing them to do well, wishing success on their books, I feel caught between being a critic and a well-wisher.

This reminds me of Colson Whitehead writing a negative review of Richard Ford’s short story collection, A Multitude of Sins, and how Ford later spat on Whitehead at a party. It’s an extreme example of the rancour that can come from a bad review, but it bothers me that as a writer I might have a negative impact on another writer’s work and life. I might be on the edges of it, but I can already see there is a community and camaraderie amongst published writers.

It’s good to write critically about a piece of art, but as a writer who meets other writers, who supports other writers, who acknowledges that there are different strokes for different folks, how can I write negatively about a book that I want to do well? Am I being cowardly? But also, how can I write positively about a book when I am perhaps good friends with the author? Can people trust my review?

It feels like there should be a separation of concerns. I know authors need to take criticism, but do they need to give it out? Perhaps they do. I’m still very conflicted on this.

On writing ‘The Complex’

The first shoots of the ideas that would combine to become The Complex appeared way back in November 2012, when I was fascinated by Lars von Trier’s film, Antichrist. I hadn’t watched it, I was too scared of it, but I was reading interviews with Charlotte Gainsbourg about what it was like to work on the film, and I became fascinated with the idea of going into the woods, with actors, as a director, and getting them to do whatever I wanted. I was suffering with writer’s block at the time. To be able to write freely, without censure, in a cabin in the woods on my own internal film set, was an exciting idea. I was crushing the life out of myself with old feelings of shame and inadequacy. Gainsbourg in the interviews made film-making with extreme material feel playful. I wanted some of that.

I didn’t write the first words of the first draft of The Complex for another three years. By this point, in December 2015, I was in the middle of the second year of an MA in Creative Writing at Manchester Metropolitan University. I had been flailing around creatively, with two aborted attempts at a novel on my desktop, but now things were getting serious. For the first time, I had workshops in which I had to present work from my final dissertation, a novel, to a group of my peers and my tutor. I remember reading back through years of notebooks, pulling together strands of thoughts and little sketches, about a cabin in the woods. I also found notes I had made about the psychoanalyst Carl Jung, taken after my mother died in 2014. In working through my grief, I had written about his concept of a complex, in which a person is taken over by patterns of thoughts and feelings so that they act irrationally, with great energy.

I had even written in my notebook that The Complex was a perfect title for a novel. I had forgotten all this, even when starting to write two other novels, but now, when I needed it, the title reappeared. I think I fell into a complex to write the first half of the first draft of the book — after years of not being able to write a longer story, under the pressure of a workshop, with a tutor who I wanted to impress, the words started to come. Three voices — Stefan, Gabrielle and Leo.

It became clear that I needed to find a narrative mechanism that would let me write more fantastical, dream-like sequences, but staying grounded in the emerging location of the story. They appeared organically, as I wrote the draft. Stefan has the Virtual Reality headset. Gabrielle has Art’s drugs. And Leo has whatever is in the place itself.

And I wanted to explore relationships. These characters were parts of myself, and I could bounce them off each other, let them rip. A lot of the fun of writing The Complex came from imagining the scenes as if I were shooting a film. My father introduced me to genre stories very young. He loved mysteries, thrillers, fantasy, science-fiction and horror, in books, television and films. Growing up, our house was totally liberal in what I could read, mostly liberal in what I could watch on TV, but totalitarian in terms of having and expressing feelings. No wonder I had writer’s block. But that’s an entirely different blog post.

When the writing was going well, it felt like I was making a film for myself, perhaps for my father too. Dreams, fantasies and the imagination are all real in their affects. Through Gabrielle I could write about my grief at my mother dying, Stefan about optimism and hope, and Leo about desperation, longing and despair. It felt like important work to be doing — even if it might never be published.

Because the book took almost four years to write, by the end of it I was a different person, and I could look more clearly at the themes. There was grief, yes, but also the problems of intimacy, technology, sanity and reality, family, falling in love, betrayal, addiction, competitiveness, manipulative relationships, affairs, and memory. I’d covered a lot of ground, but organically, without a conscious agenda. The story is driven by the characters. In writing, the themes seemed to follow the characters interests, but if I am the characters, and they are aspects of myself, then I guess these were all my concerns and obsessions.

Anyway, my tutor on the MA was Nicholas Royle, who was also a commissioning editor at Salt. I feel lucky and grateful that it will be published and read. Now I have to write some new characters, in new locations, and find out how my obsessions have changed. It’s like writing myself into existence.

Since I’ve put it like that, I’d better crack on.

High Rise

I read several Ballard books in the late nineties — my mid-twenties — starting with short stories, before being entranced by the original shiny silver paperback cover of Super-Cannes, and then going back to his earlier work. When I saw there was a film of High-Rise being made I believed I’d read it, but when I bought a copy, apart from the general sense in most of Ballard’s stories of things being on the edge of primal chaos, I didn’t recognise the story or characters at all. I’d read so many of his book shop blurbs they had all blurred together. In my twenties I didn’t read with much real attention either so it was quite possible I had read it and just forgotten everything about it.

Robert Laing is a newly divorced medical academic who moves onto the 25th floor of a high-rise block hoping for a life of comfortable anonymity. Richard Wilder lives on the 2nd floor and makes television documentaries. Anthony Royal is the building’s architect and lives in the penthouse. These three characters are rotated by Ballard to tell the story of the building, which is seen as a mixture of designed technology and living organism. It’s a social experiment designed by Royal and embraced by every resident at every level. Where Laing is a social chameleon who wants to make a safe place for himself in the building, Wilder wants to conquer it and confront its maker.

If the high-rise is a living thing, a psyche, and Ballard its ultimate creator, the three protagonists could be different aspects of Ballard’s creative personality. Each man tries to make the building serve them in their own ways but it’s the women who ultimately make the place theirs. The prose mixes an omniscient point-of-view with that of the character Ballard is following in each chapter. It is only at the end, in the final confrontation between Royal and Wilder, that he moves between both characters point-of-view in the same chapter. The author’s omniscience could easily be the building’s point-of-view, but at the same time I found it a little irritating how characters revealed chunks of backstory in their thoughts. Having said that, the descriptions are brilliant and unnerving. Ballard is very aware of the spaces his characters inhabit and finds endless ways to show the collapse and degradation of their initially modern and comfortable environment.

I was nervous about watching the film. The book was so particular and the opinions I had read were mixed, but more than that, I didn’t want to subject myself to two hours of disgust and misery. Perhaps from this starting place I was always going to enjoy the film more than I expected but that is to do the film an injustice. It is an excellent story in its own right.

Directed by Ben Wheatley and adapted by his long-term screenwriting and editing partner Amy Jump the protagonist of the film is definitely Laing. Wilder and Royal are still important characters but Laing is given far more agency and the narrative is quite different. It feels like the book is honoured though, and I suspect that is because while Jump makes the story more dramatic and brings different characters to the fore, in particular the female ones, Wheatley’s direction creates the equivalent of Ballard’s prose style in the visuals and soundtrack. It’s an impressive feat.

As stimulating as the last two weeks have been for me in the world of High-Rise whatever I read next needs to be a palate cleanser. A nice rom-com perhaps. No roasted dogs.

Written on the Body, Let the Right One In

Week 1. I’m going to try to read a novel and watch a film each week in 2018. In time, I’ll work out what I’m doing with it. We’ll see if it sticks. I love the idea.

Written on the Body, Jeanette Winterson (1992).

Let the Right One In. Dir. Tomas Alfredson, 2008.

I tried to use these in my practice week and failed utterly, because Christmas. I’ve been up and down the country, making food for people, visiting people, people, people, people. There has been no time or space.

But I’m home now, and I want to create that time and space. It’s important. I might be biting off too much, but let’s give it a go.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a way of exercising your ability to pay attention: when you can focus on something, the critical thoughts quieten down.

– Ruby Wax, Frazzled