Michael Walters

Notes from the peninsula

Farewell, 2021

As 2022 comes into view upriver, the final days of 2021 flow past, and I couldn’t pass up the chance to reflect on what I’ve read, watched and written this year. (Okay, reflect is a strong word, but it’s been a difficult Christmas, and I’m very tired.)

In books new to me, I opened the year with Ali Smith’s wonderful Autumn, and if my favourite books are like stepping stones on this river metaphor I’m in danger of drowning in, from there I went to An Awfully Big Adventure (Beryl Bainbridge), The Cost of Living (Deborah Levy), Clothes, Clothes, Clothes… (Viv Albertine), Redhead by the Side of the Road (Anne Tyler), Boy Parts (Eliza Clark), Hotel du Lac (Anita Brookner), The Shooting Party (Isabel Colegate), and The Glass Hotel (Emily St John Mandel).

I’m not much of a re-reader, but I got caught in some reading ruts this year, and I found writerly solace in returning to Joyland (Stephen King), Annihilation (Jeff Vandermeer), and Tinderbox (Megan Dunn).

Films. Oh-so-many films. Out of [165 films watched in 2021(https://letterboxd.com/michaelwalters/films/diary/), I gave 39 of them a rating of 5/5, and of those, my top 10 favourite discoveries, in chronological order of being made, are:

- Blow-up (1966)

- Performance (1970)

- Klute (1971)

- The Long Goodbye (1973)

- Blue Velvet (1986)

- Lost Highway (1997)

- Triangle (2009)

- Riders of Justice (2020)

- Pig (2021)

- Dune (2021)

And because this image blows my mind, here are all 165 from Letterboxd, in reverse order of watching:

Finally, in my writing, I started the year with 25,000 words of a new novel, and I end the year with 22,000 words of a new novel. But I’ve already written enough about that.

The great adjustment

Between January 2018 and December 2021, I watched 569 films. I know this because I track the films I watch on Letterboxd. That’s a lot of films. Not as many as more serious cinephiles, but a tremendous amount for someone who actually wants to be a novelist and not a filmmaker. I‘ve watched 157 films this year so far, which is on average fifty minutes a day, the length of a session of psychotherapy.

There was a gradual increase—2015 (11), 2016 (34), 2017 (61), 2018 (140)—and it’s linked to submitting my novel-as-dissertation in September 2017. After that, I needed to get away from writing, so I discovered horror film podcasts, and started a completely different adventure. I told myself that it was useful, which it was, to understand how the great (and not-so-great) films worked, thinking about story, narrative, dialogue, character arcs, all that good stuff, but looking back, I should have disengaged earlier and brought that knowledge back to my writing.

When the pandemic hit, and I was stuck working at home in a new job, with a constant newsfeed of virus fears, Trump and Brexit, I doubled down on films as a coping mechanism. (I know I keep going over this, but I think a lot of us are going to be dealing with a form of PTSD around the pandemic experience for some time to come.) I stopped reading for pleasure, partly because I lost my commute, and partly because I could feel a pressure building in me to be writing the next thing. I could watch a whole film in a ninety-minute evening slot and tick it off a list, but a novel was a longer undertaking, over several days, taking up valuable headspace that I could be using for writing. I would pick up a book, and quickly have to fight the urge to scan it, study it, and jump to the end. This was reading without engagement. I was still reading novels, but in a begrudging, desperate, manic, miserable way.

Films made me feel better in the world. Books made me feel worse. Films immerse you through image, sound, story and the fact you have to watch it for as long as it lasts, like a fairground ride. This intensifies the experience and heightens emotions, so it is closer to real life. I love that. But reflecting on a film is hard while you are watching it because it is still happening to you. It’s quite an invasive experience. It can feel overwhelming.

Books, on the other hand, give the control to the reader. A reader can be distracted by a knock at the door, read sentences a second or third time, look out of the window and daydream, recall a memory, read faster or slower, skip over a stressful scene, or even read the ending first. They can make notes in the margins and write in a notebook. You are immersed in the world of a book, but the book doesn’t demand your undivided attention. Books are a very forgiving companion. (I heartily recommend the chapter on reading in The Art of Rest, by Claudia Hammond.)

Here’s the heart of the matter for me: I can’t write without reading. To write, I need the written word as nourishment, and for me to feel nourished, I need to read slowly, with curiosity and my mind engaged.

This realisation, which is completely obvious on the surface, arrived because, in thinking about 2021 and what I might do differently in 2022, I looked back at the books I had read, and the films I had watched, and knew there needed to be an adjustment. I’m out of balance in how I get my story fix.

After four years of my adventure in films, I’m starting the great adjustment—fewer films, more books, and getting reacquainted with the gentle art of reading.

Keeping the story alive

Feeling the pull of Christmas, and seeing 2022 on the horizon, I’m looking at my work-in-progress, and it seems to be asking how we got here. It’s a patient and wise creature. It knows I haven’t said anything about it to anyone, bar its name to a very select few, perhaps out of superstition, but also, I think, to keep the energy it holds close to me, to nurture it, and show it I am taking it seriously. It’s not fodder for polite, or impolite, conversation, and certainly not to be talked about on Twitter.

The glimmers of this story coalesced in February 2019, while I was working on final edits for The Complex, where all I knew was that it was going to be told over several locations that I had dreamt and sketched on a map, it had a title, and most intriguingly, a revealing phrase about the protagonist. I was in a particularly manic phase of my life, because my day job was busy, The Complex wasn’t finished, and to self-soothe, I was watching way more films than was good for me. Ridiculously, I was also trying to learn German. My mind was leaping around like a loon, but I kept redrawing the map, came up with some character names and a couple of grand metaphors, and thought about character motivations. This was all between doing other life things. No draft words were written. These were just ideas I kept coming back to, with some occasional sentences in my notebook.

As an aside, I find free writing to be an essential creative writing tool, where you write without censoring yourself for twenty minutes or so. Another is writing conversations with characters in an imaginary theatre space, both as characters and the actors playing them. You can get them to rehearse with each other, improvise, and so on. Great for when you’re stuck.

Right, back to the story of the new story. For me, this is where it gets interesting. In my head, I had been telling myself that all through the second half of 2019, with The Complex being published, I was in marketing mode, spending way too much time on Twitter, asking for endorsement quotes, organising a book launch, looking for opportunities to talk in public, and all that necessary stuff. Looking back at my notebook from the time, in fact I continued to work on the new story all through the autumn, adding layers to the characters, changing their names, lightly researching the things they were into, drawing and redrawing the map, cutting out photos from magazines, and continuing to build up the world. I suppose I thought I wasn’t working on it because, looking back, there was no tangible progress, no words in a draft, but I’m way too hard on myself. Novels take the time they need, and life had to come first.

Then in February 2020 I started a new job, and the world went a bit mad.

I kept writing in my notebooks. I wrote a short story, Signal, which was published by Nightjar Press. Work was incredibly challenging, both kids were home from school, the line between work and home disappeared, and the news was full of the pandemic, Trump and Brexit. I watched a lot, a LOT, of films. It began to feel like I had writer’s block again, but I kept writing in my notebooks, and the make believe world slowly solidified.

When the cafes opened again in August 2020, I began a first draft. I was up to twenty thousand words when the second lockdown hit. I got it up to twenty-five thousand by Christmas, but the third lockdown, the big one of January 2021, totally messed me up. I retreated to my notebooks once more. (I seem to need a cafe to write a draft. It’s the only place I am guaranteed no interruptions. And home is now where I do software work.) For seven more months I wrote in my notebooks. Finally, in July 2021, I went back to the beginning of the draft, and in my little Caffe Nero, every morning before work, I edited it into some sort of shape.

What am I trying to say? It’s over two-and-a-half years since I started this next novel. It’s becoming real at last. I’m praying there are no more lockdowns, but perhaps I’m too far along now, with too much momentum, for another lockdown to block me. My notebooks helped me keep the story alive through the chaos. They are also the custodians of the facts of the story’s writing, its history, because I really can’t trust my memory.

I’d like to have a completed draft by my birthday, in March, which would be three years from inception. That appeals to my sense of neatness. And if it isn’t already abundantly clear, I write in my notebook every day. That’s what makes me a writer. It’s nothing to do with word counts or being published. It’s showing up in a notebook and keeping the creative flame alive.

Horror AND sex!

Here we go again, with my fourth #31DaysofHorror extravaganza/exhaustathon. This year I just want a reason to watch a lot of horror films. Here are the rules I’m playing by:

- one blog post about a horror film on each day in October

- the posts must be published in the order the films are watched

- the film must either be completely new to me or not seen in at least twenty years

- to stay healthy, the challenge starts twenty-one days before the first post is published

I’ve talked about this before, but watching these sorts of films makes me feel like I’m hanging out with my dad. When I was eleven years old, on a rainy afternoon in a Saundersfoot caravan park, to stop me complaining about being bored, he let me read his copy of Salem’s Lot. On the same holiday, in a Tenby second-hand book shop, I bought Guy N. Smith’s Night of the Crabs because the fantastically lurid cover grabbed me, and in the back of the car on the way home, with a furtive look around to make sure nobody could see, I came across my first literary sentences about sex. Horror AND sex! (Let’s ignore that it was about crabs.) I was off to the races.

Around the same time, a VHS recorder arrived in the house, and the video shop became one of my best friends. Both my parents were incredibly liberal in what they let me watch—thrillers, horror, sci-fi, fantasy—and my dad started to introduce me to less well-known films, and eventually I discovered Moviedrome, that beloved late night BBC Two haven for cult film lovers.

Genre stories were my magic carpet. It’s shocking what I was allowed to watch (and read), but those films kept me company. They were a comfort and an outlet for my adolescent horror show. Later, once my son was born, I couldn’t watch horror films, because the world had become scary enough, and post-9/11 there was a lurch towards torture porn, which I hated. I only returned to horror recently, in my late mid-forties.

The 2020 challenge was a lot of fun. I did that one to stop the Trump/Brexit/Covid shitshow from filling up my head (there’s a list of the films from 2018 and 2019 there too). #31DaysofHorror started as a dare to myself, then became a protective mechanism against watching too much news, and now seems to have settled into a fun ritual. I think I know what my first film this year is going to be.

Stop rushing

Time isn’t real. The future is an abstraction. So says Alan Watts. I do rush things to get to the end of them—not always, but often enough for it to be a thing I’ve noticed over and over again throughout my life. I didn’t rush in my twenties. Rushing is something that started for me after my son was born, when the enormous pressure of being responsible for the life of another human being hit me. That was the moment I realised that whatever I wanted to do with my life had to fit around being a father first and foremost. Children require attention, a seemingly endless amount of it, and giving it to them is one of life’s great privileges, pleasures and sacrifices.

I can say truthfully that I did not rush my time with either of my children. I did a good job of being present with them and really experiencing fatherhood. The same with being a husband. I suppose it’s because I valued relationships, emotions and connection over my career, ambition, money or status. I don’t think I got the balance right, but at the same time I did the best I could with what I had. Perhaps that’s a psychological sleight of hand to make myself feel better about it. I don’t know.

I followed my father and grandfather in being a technician rather than a manager. I spent large portions of my time thinking about what to do rather than doing things. I didn’t keep up old friendships. I stayed in jobs for long periods of time rather than working my way up any ladders. None of these things were mistakes, though they sometimes feel like that, but they were choices, whether I was conscious of them or not.

All of which is to say, I am here, with this life behind me, and possibilities ahead. In this moment, writing this post, I am choosing not to rush, but instead listening to what I want to say to myself and letting the words flow through my fingers. Before starting to type, I was worrying over what film to watch, what book to read next, whether to push harder at the story I’m trying to finish for the end of the month, or if I should do yoga, crack through some chores, or worst of all worlds, start browsing through Twitter. Actually what I needed to do was sit quietly and listen. And here we are.

A seat in the sun

I’m sitting in the sun. August isn’t going to plan, but I’m doing the best I can with it. I won’t go into the details, we all have work and family dramas that flare up when we least expect them, but it means my focus on writing is suffering, and I might need to pause things to concentrate on what else needs to be done. C’est la vie.

But there is a short story I’m in the middle of writing, and it might want to be finished no matter what I think is sensible. If I commit to it, I will finish it, but at the cost of other things. I’d rather do everything I want to do. Of course, right? I don’t want to make the decision to stop writing too early—it might all come together if I keep it alive in my mind—but walking the line of what’s possible and not is both precarious and uncertain. Hell, writing is an ambiguous process at the best of times.

I’m doubtful, and it all seems like an intuitive rats nest, but I think I’ve talked myself into the juggle. To sail on and tack into the wind. Well, alright then.

Why read?

It’s been a tough year, and in the tumult of it, I stopped enjoying reading. Instead, I watched films, which are just as wonderful, but do a fundamentally different job. If you feel jaded with reading, or you want to think a little more deeply about what it means to read, I recommend the book I dug out this week, a collection of short essays, Stop What You’re Doing and Read This!.

I took some notes for myself and thought here was as good a place to put them as any.

‘A trained mind is a mind that can concentrate.’ – Jeanette Winterson

When we read a book we create a unique experience for ourselves from the words, like a musician does with a piece of music. The brain falls into a trance-like state and to our minds it is as if the events are really happening. Strong emotions alter the brain, so reading physically changes us, and in reading we can discover parts of ourselves we didn’t know existed. It can also simply be an escape from daily suffering. It’s a relief to find out other people have similar thoughts and feelings to us, and we are not alone.

It’s thrilling to be transported to another world. The right book is a question of taste and timing. It’s important to love language – this is where books are different from films. Words convey inner experience in a way that film cannot. We can inhabit novels and become friends with them. Poems can be life-saving to people in the depths of despair and sharing our experiences of reading builds groups and communities.

Tim Parks says modern life is fast and there is pressure to rush, but rushing ruins reading. The opening pages of a book show the author’s intent. Writers use the tricks of language to get into our heads, so don’t be a pushover and be ready to walk away. Pay attention and think critically. The perfect mode of reading is a kind of wakeful enchantment. Reading critically is a question of self-esteem.

Jeanette Winterson describes the imaginary world of books as ‘the total world’, holding the inner and outer as one whole. Time isn’t linear in books, just as it isn’t in memory, where we group things by meaning and symbolic power. For her, reading is a way of being at home in her own mind. It’s ‘a private conversation happening somewhere in the soul’. She says books work from the inside out and balance the work we have to do in the world to survive. Art (and writing) is a medium for the soul, so find books that have being, is-ness, vitality.

Something Wicked This Way Comes

I bought Something Wicked This Way Comes three years ago in a bookshop sale, in spite of the cover, which honestly put me off reading it for a long time. It showed a terrified, wide-eyed carousel horse looking down, about to trample the reader under its feet. When I did start to read it at the end of last year, I was surprised by the lyrical, slightly opaque language of the opening pages, and I put it down. It was so unlike the straightforward prose of Fahrenheit 451 (1953), I was disappointed.

I’d read Fahrenheit 451 three or four times over the years, but I didn’t know much about Ray Bradbury’s career or other works. I wondered what he’d written in the nine years between Fahrenheit 451 and Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962), and it turns out he tried to write a semi-autobiographical novel about his childhood, which became a short story collection, Dandelion Wine (1957), and he published other collections of stories he had written as a younger man in the 1940s. I’d like to read his biography, because reading behind the lines of Wikipedia, it looks like he spent most of the 1950s recycling older material for a new, much larger audience. He would have been in his thirties in that decade, and I wonder if he found that period frustrating.

(I’m possibly projecting. Megan Dunn writes brilliantly about her long relationship with Fahrenheit 451, and her own creative frustration in her memoir with Galley Beggar Press, Tinderbox (2017).)

Anyway, out of that decade, galloping out of the gate, or rather accelerating around the carousel, came Something Wicked This Way Comes. Bradbury had just entered his forties when this was published, and it gives a mostly-child’s-eye view of the arrival of an evil carnival in Green Town, Illinois.

A couple of weeks ago I decided to give it another go. I tweeted a picture of the cover, perhaps looking for some public accountability in making myself read what I knew was a classic, and I was thrilled by people’s replies with their own different-covered copies. Even in my small literary circle it was loved.

It’s a story about the perils of youthfulness and mid-life. Young teenagers Will Holloway and Jim Nightshade watch the Coogar and Dark carnival arrive in the middle of the night. In a series of breathlessly narrated, yet lyrically rich, set pieces, they see more of how the carnival works than they should and are hunted by carnival folk over a long late-October weekend. The carnival feeds on fear and pain, and tempts people with their deepest wishes. Only Will’s father, a janitor at the local library, himself full of doubt and regret, believes their story.

That accidentally reads a bit like blurb on a back cover, which is probably because I loved this book. The secret to getting into it was to read it fast and let the language pour over me, not sweating the sentences too much, and being carried along. Some scenes are all-time classics I’ll never forget — the boys hiding under the grill of the cigar store as the carnival marches through town; Mr Cooger being shocked under the policemen’s transfixed gazes; Mr Dark arriving at the library looking for the hiding boys.

Youth is hard, and getting old is harder. Every choice comes with a life not lived. My father was an older man, about Mr Holloway’s age when I was like Will, and now I am a father myself. This book hit home.

A flotilla of metaphors

Lying in bed this morning, between the alarm going off and me pulling back the duvet, it occurred to me that sentences can capture the high-level aspects of a story as well as the nitty-gritty. This isn’t a world-shattering realisation, and it isn’t like I’ve invented a vaccine or anything, but for me it was a little spark, a sympathetic prod, a loving poke even in the direction of writing enlightenment.

When the creative winds are not blowing, and you find yourself becalmed, those summarising sentences can be like flying a kite high enough to catch a draught that might pull your flotilla of metaphors to fresh coordinates.

Writing gland

Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft is one of those books I keep coming back to, this time to stimulate my first draft writing gland and get my novel moving again. I’d run aground at twenty thousand words. King’s advice? Write every day and keep going. Thanks, Stephen. Annoyingly, he was right, and I wrote 500 words every day this week. Yay, me.

Even with this blockage removed, and perhaps because the blockage wasn’t there to fixate on, it was a tough week, the hardest emotionally since the pandemic started. This time we know it will be months, not weeks. Outside it’s cold, dark and icy, and I turn forty-eight in March. The life clock is ticking.

To inject some fun into things, I watched Tentacles, a B-movie Jaws ripoff starring John Huston (!), Shelley Winters (!!), Henry Fonda (!!!) and Bo Hopkins (?!). It was much worse than I hoped. Where [Piranha had Joe Dante to add some humour and irony]({% link _posts/2020-31-days-of-horror/2020-10-10-piranha.md %}), Assonitis is seemingly incompetent. All those great actors wasted. Where did the money come from to make this? I’m glad I watched it though, because I never take a complete punt on a film like this, and now I know what a terrible B-movie looks like.

Clearly a glutton for punishment, I went Thai aquatic horror next with Brian Yuzna’s Amphibious, a.k.a (which I only realised after a completely unnecessary battle axe was hurled at the camera) Amphibious 3D. My eyeballs were still seared from Tentacles, so as poor as the script and acting were, this felt like a banquet of cinema in comparison. The giant sea scorpion was memorable, and the Miskatonic University sticker on marine biologist Skyler Shane’s laptop made me smile. It had an odd tone, like a gory mix of Big Trouble in Little China and Pirates of the Caribbean. I can’t recommend it.

After those two stinkers, and also being primarily a writer of novels, it seems wrong to bring in 2020 Booker shortlisted Real Life here, but that’s how the week unfolded. Like real life, Real Life is impressive but left me frustrated. The book’s protagonist, Wallace, is similar to me in some ways (emotionally damaged, male, scientist) and not in others (he is black and gay). Over an intense weekend, we see his previous experiences and assumptions spark against those of his friends and colleagues. My problem with the book is too many times I felt overwhelmed by, and impatient with, the cattiness, games and histrionics of his friends and peers. Perhaps it’s where I am in my life. I’m glad I’m not in my twenties anymore. Perhaps I’m jealous — he didn’t even want to write a novel and wrote it in five weeks just to get his agent off his back. Damn it, Brandon, at least pretend it was hard.

It is, of course, Giallo January, and like Taylor, Dario Argento is prolific (yes, I see the pattern in my choices here). After Argento’s debut masterpiece The Bird With the Crystal Plumage came out in 1970, he released two more films in 1971 — The Cat o’ Nine Tails and Four Flies on Grey Velvet. The former is a sprawling crime mystery set in Turin and has a blind ex-journalist join forces with a reporter on a big newspaper to solve the murder of a scientist at a genetic research facility. The latter is more in keeping with Argento’s other work, where a serial killer torments a rock musician and makes him question his sanity. There are red herrings galore, and lots of over-the-top and super-camp side characters, but for me these films are about striking images and what can be done with a moving camera. They both drag a little in places, but more than make up for it in extended bursts of suspense and action.

Argento demonstrates the power of looking and framing what you see. Both Argento and Taylor create impressive works at pace. Yuzna is enthusiastic and professional, even when he must know the problems with his script. Assonitis is ambitious and knows what sells. Let’s funnel energy from these unlikely role models into the week ahead.

- On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, Stephen King (2001)

- Tentacles, dir. Ovidio G. Assonitis (1977)

- Amphibious, dir. Brian Yuzna (2010)

- Real Life, Brandon Taylor (2020)

- Four Flies on Grey Velvet, dir. Dario Argento (1971)

- The Cat o’ Nine Tails, dir. Dario Argento (1971)

Slippery surfaces

I started the week with Blade Runner 2049. I was frustrated with it in 2017, but watching it over three nights at home, I’m more forgiving. It’s way too long. It looks beautiful, and it has some fascinating ideas, but the story is broken. The main villain disappears without much comment, and I didn’t buy the replicant rebellion, so the idea of K sacrificing himself had little emotional weight. It’s disappointing. There’s an interview in which Ridley Scott gleefully claims to have been heavily involved with writing the script, which might explain a few things. I did find K’s relationship with his home AI moving. She felt like the heart of the film. It’s a glimpse of what could have been.

(Am I doing weekly summary posts now? Perhaps I am. It helps me notice what impact the week’s books and films have had on me. Hand-written notes just get lost in the stream of ink on paper.)

My Year of Rest and Relaxation, by Ottessa Moshfegh, left me cold too. I admired it — the prose craft is superb, and it had funny moments, but I got bored and ended up skimming the final third. The unnamed protagonist had similarities to Eileen, Moshfegh’s previous novel, which I really enjoyed. This felt more like one of the art projects she satirises. It almost became another one of those books that snarled up my reading rotors in 2020, but I spotted the danger and switched to speed reading mode. I’m high-fiving myself for that.

From there, I jumped into The Man Who Saw Everything, by Deborah Levy, which was a lot more interesting. Her prose is impressive, with a formal air, possibly because she tends to write characters with academic backgrounds. I remember there being a surprising amount of dry economics and politics in Hot Milk, although that it’s been a while since I read that. She manages to make Saul Adler both sympathetic and unpleasant in his perfectly justified narcissism, and the ending felt suitably weighted and emotional. She makes the jumps in time pay off.

I closed the week with three sparky films. In Spontaneous, Brian Druffield somehow managed to make a film about high school students spontaneously exploding be funny, romantic, horrifying, sad and hopeful. There is a definite feel of a school shooting about the randomness of people dying in front of you, but the central relationship is sweet, and Mara is a fantastic comical and complex teenager (a stellar performance from Katherine Langford). It also feels right for COVID times.

The Woman Who Ran couldn’t be more different. In the suburbs of Seoul, Gam-hee visits old friends she hasn’t seen in years because her husband is away. She tells them she is happy, but this is the first time she has left his side since they were married, and we sense mixed feelings under the surface. It’s like she is trying on her friends lives to see if they are a better fit than her own.

Finally, swayed after a glass of wine by the superlatives in the Mubi description, there was All the Vermeers in New York, a weird, awkward independent film from 1990, that mixes a slightly grating jazz soundtrack with shots of New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, paintings by Vermeer, conversations between students who somehow share a ginormous flat in Manhattan, an aggressively out-of-place interaction between an artist and a gallery curator, and a stockbroker who has fallen in love with a student half his age. It’s one of those messes I’m glad I experienced, but I can’t recommend.

- Blade Runner 2049, dir. Denis Villeneuve (2017)

- My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Ottessa Moshfegh (2018)

- The Man Who Saw Everything, Deborah Levy (2019)

- Spontaneous, dir. Brian Duffield (2020)

- The Woman Who Ran, dir. Hong Sang-soo (2020)

- All the Vermeers in New York, dir. Jon Jost (1990)

Autumn and The Long Goodbye

In Ali Smith’s Autumn (2016), when discussing a piece of art, Daniel Gluck asks the young Elisabeth, ‘And what did it make you think about?’. I love the openness of that question. Interpreting art is about making connections. There is a passage where Daniel describes to Elisabeth a collage by a long-forgotten artist, and when I ask myself what Autumn makes me think about, my first answer is — a collage.

I had read that this was a contemporaneous novel, written very quickly over the summer of 2016, in the aftermath of the Brexit vote, but reading interviews with Ali Smith, it was more complicated than that. She had partly written another novel, which also made its way into Autumn, so she must have been writing new material into the structure and details of old material. The story jumps back and forth through time, so you are left with a sense of having looked through an artfully assembled non-chronological series of scenes, much like a collage.

This helped me with my work-in-progress, which slowed to a stop over Christmas. I can imagine Ali Smith standing over a canvas, sticking a scene here, a scene there, gleefully assembling pieces she had written out of order into a final draft. I’m envious of the flow state artists get into. Quick decisions. Instinct. Collaging also reminds me of how a jigsaw comes together. Repeating themes.

The Long Goodbye (1973) was released the year I was born. I guess I’m thinking about births and deaths — I heard a vicar on TV describe the circle of life as ‘hatched, matched and dispatched’ — and time passing. It’s a stunning film noir. Elliot Gould is a pathetic, melancholy Philip Marlowe, pushed and pulled around, desperately loyal to his friends. By the end, that loyalty is exposed as his weakness. The climax is surprising and cathartic. The story’s character work pays off. It’s like a novel in the way Marlowe constantly talks to himself, revealing his inner world. No matter what eccentric scene he comes across, he reflexively says, ‘It’s okay with me’. Until finally, it is not okay.

- Autumn, Ali Smith (2016)

- The Long Goodbye, dir. Robert Altman (1973)

My 2020 in books

I’ve had a tough year reading books. I fell into the trap of seeing reading as work and lost the joy of it. I filled the story gap with films, but thanks to a throwaway Goodreads challenge (35 books in 2020), managed to keep going. Writers aren’t supposed to admit to not enjoying reading. It’s a truism that reading is a necessary part of writing, but in agreeing to go to a new book club, reading Adelle Stripe’s Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile became actually necessary. I would never have chosen it, but I’m happy I did, because the writing was brilliant, and showed a way to use fiction to tell the story of a real person, in this case the playwright Andrea Dunbar. Dunbar died in 1990 from a brain haemorrhage. It made me think about poverty, alcoholism, bad parents, and my own working class roots.

From there I turned to a H.P. Lovecraft collection, The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Tales. Most books I choose are novels, and if I do choose short stories they tend to be smaller collections, so this hefty tome, with several novellas of increasing conceptual density, became a serious obstacle. Instead of putting it back on the shelf, I let it sit on my desk making me feel guilty, because it turns out part of my personality requires that I finish books I start. I’ve always been a one-at-a-time book guy, and if a book becomes dull I skip and scan ahead, but those tactics didn’t work here. I ran aground just over halfway and stayed there until the end of March.

Stoner, John Williams’s classic, got me off the rocks and back on track. It’s one of my favourite books of the year, a view of a man’s life from birth to death, concentrating on his time as an academic at the University of Missouri — a simple man with a straightforward life, and all the wonders that entails. At the end of April I hit another book that knotted up my reading propellers — Rebecca, by Daphne du Maurier. I really didn’t like it, even though my peers seemed to unanimously love it, so I kept trying to finish it, and I kept sabotaging my own efforts. A grim period. Perhaps that first lockdown was getting to me. Eventually, like Lovecraft, I put the old woman aside, and switched to a burst of science-fiction.

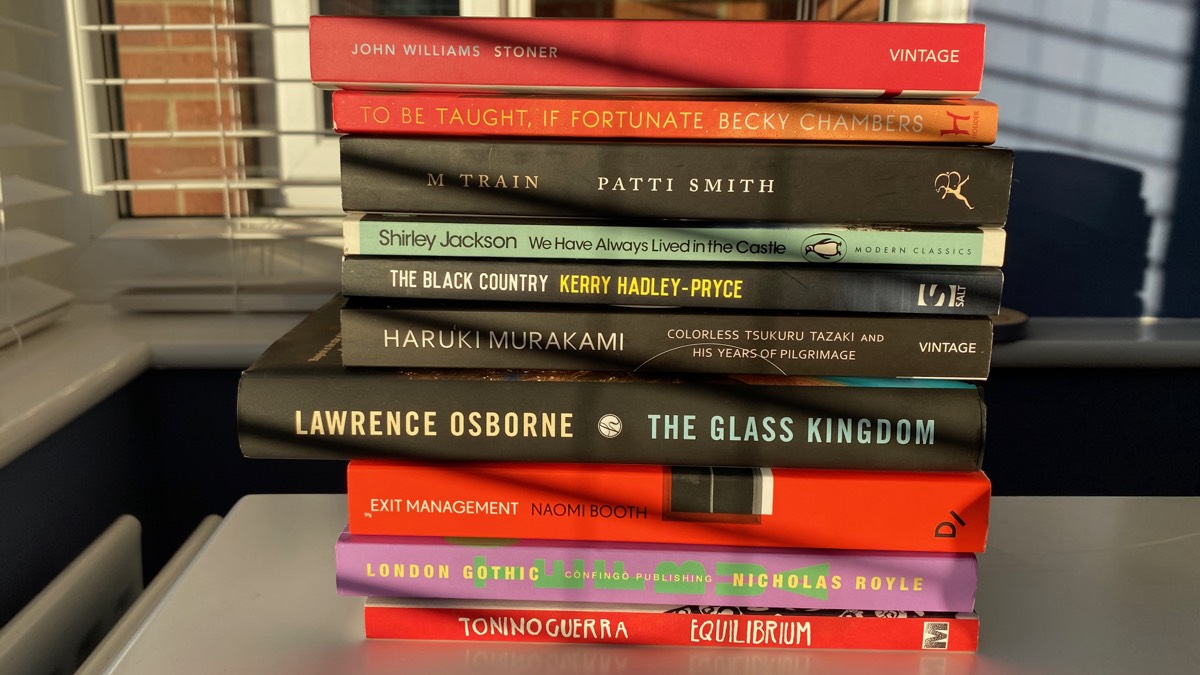

Someone recommended To Be Taught, If Fortunate, by Becky Chambers, on Twitter, I liked the idea of a novel about astro-biologists, and it was short. I’ve always found short novels to be the best route out of reader’s block. Each chapter sees the crew of a deep space mission to investigate life in the furthest reaches of space stop on a planet and study its biological wonders. The pleasure is in the atmosphere, descriptions and crew dynamics. From planet Chambers, I ventured to Shirley Jackson (We Have Always Lived in the Castle), Patti Smith (M Train), and Kerry Hadley-Pryce (The Black Country), three voices that couldn’t be more different, but lit up my summer. In August, I read Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, by Haruki Murakami, a familiar style, and a familiar Murakami protagonist, but expertly done.

My third literary roadblock of the year was Ted Chiang’s Stories of Your Life and Others. It’s lauded as one of the best science-fiction story collections… ever. The film Arrival, which I loved, was based on one of its stories, Story of Your Life. A co-worker raved about the collection to me. But, oh, how I hated this book. It wasn’t a rational reaction. The stories were beautifully crafted, and I admired them, but the ones I read were cold, empty things. I can’t think of a book that has ever repelled me so strongly. I couldn’t allow myself to give up, so it became this noxious presence on my desk for weeks and weeks. After a while I resented its very existence. I despised it. I wonder now if I was putting on that book something of myself that I was struggling to bring to consciousness. I must have been. The book was praised, successful, expertly crafted, oh-so-clever, but the characters were ciphers for ideas, and there was no discernible heart. I found the opening stories so cold they somehow froze my mind so I couldn’t continue. Eventually, I let the book go. I’m still not sure what my emotional storm over it was about.

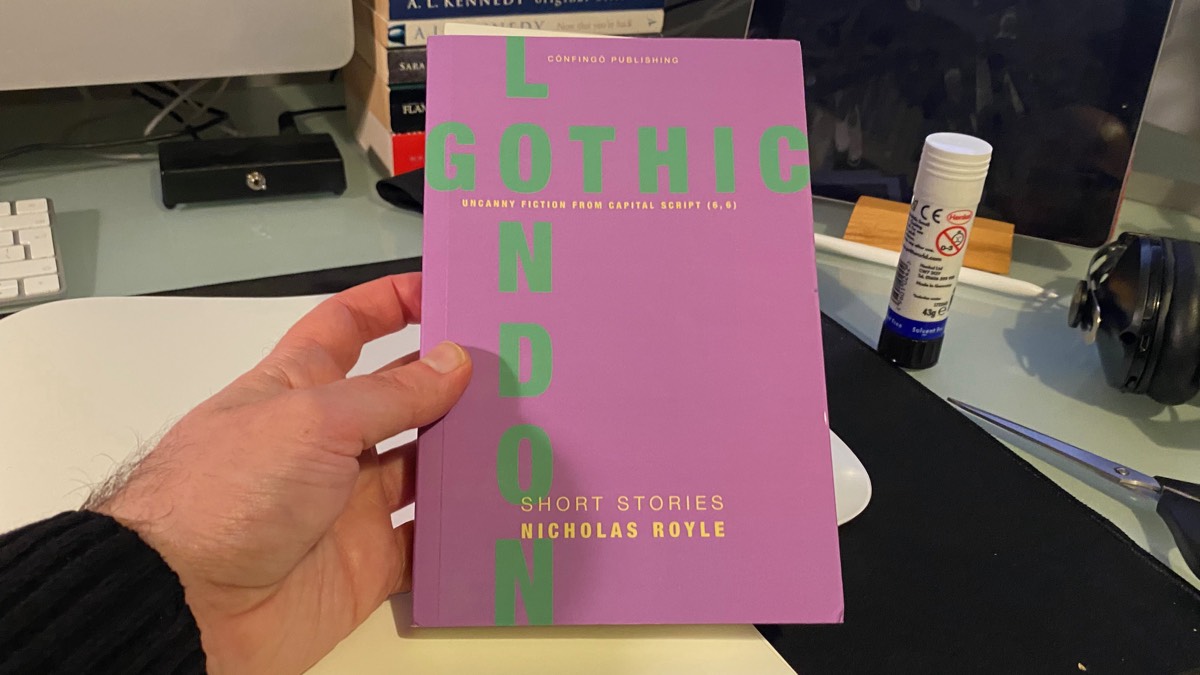

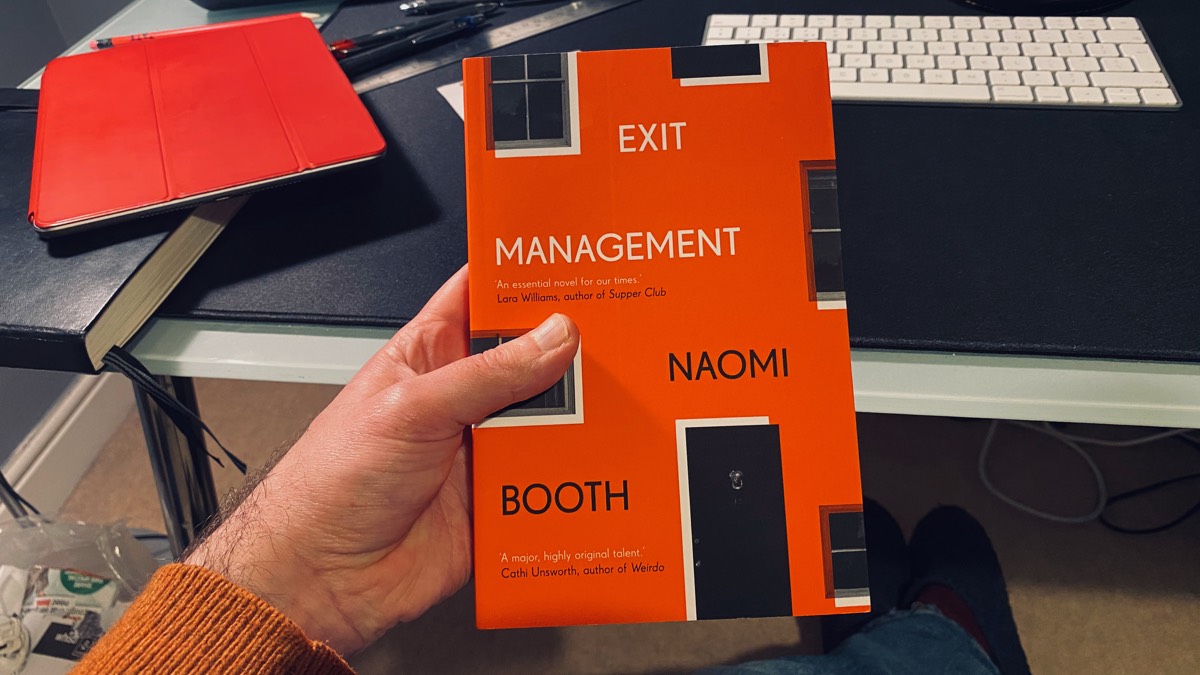

This left me running well behind schedule in November. Luckily I hit a rich vein to get me over the finishing line — The Kingdom, by Lawrence Osborne, was a cold thriller set in a humid Singapore, and inspired me to get back on the writing saddle. Exit Management, by Naomi Booth, reminded me what amazing things can be done with voice. London Gothic, by Nicholas Royle, is another of his story collections around a theme, and testament to good prose, writing about what you love, and playing the long game. Anf finally, Equilibrium, by Tonino Guerra, a firecracker novel of ideas that got me thinking about literary form and the role of history in character’s stories.

That was my 2020 in books. Next year I want to read 60 books (!), some newly published (yes), and most importantly, enjoy reading more (YES). (Note to self. Stop believing hype and make up your own mind. If you’re stalled or bored, put that fucker down and find something you’re into. It’s not like there’s a book shortage. Ffs.)

- Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile, Adelle Stripe

- Stoner, John Williams

- To Be Taught, If Fortunate, Becky Chambers

- We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Shirley Jackson

- M Train, Patti Smith

- The Black Country, Kerry Hadley-Pryce

- Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, Haruki Murakami

- The Kingdom, Lawrence Osborne

- Exit Management, Naomi Booth

- London Gothic, Nicholas Royle

- Equilibrium Tonino Guerra

Language muscles

Having watched so many films this year, next year I want to get back to reading novels. Films do play into my writing practice. They show me patterns of story, character arcs, themes and dialogue, as well as feed my imagination with striking imagery and interesting locations. Fiction has these, but is the equivalent of sheet music, so it is on me as the reader to make them real in my mind, and adds all the wonders of language — point-of-view, voice, descriptions, internal experiences, and literary forms and techniques. I’m finding reading difficult again because I’ve neglected books. Reading fiction requires reading muscles, and writing fiction requires writing muscles. To get through the horrors of 2020, I’ve let both atrophy.

Fiction also provides distance. I love reading a couple of pages and stopping to look out the window, so the words can sink in. I drive the pace when I’m reading. Films are designed to be watched in one sitting, preferably in a cinema, and the pace is out of my hands. I can reflect along the way with a book. It’s a dozen hours or more of story in small chunks. After a film I have to process the whole, and if I missed a key line of dialogue, or I’m distracted for a couple of minutes, it might leave me with a completely wrong understanding. I often leave films feeling drained, physically and emotionally, especially the longer or more intense ones.

All of this is to say, I need to get a better balance of literature and film in 2021. Language is the raw material of my art. But films are still terribly important to me.

If you listen to podcasts and love films, I can’t recommend enough the Pure Cinema podcast, with Elric Kane and Brian Saur. This is one of the things that have kept me going this year. Walking the same streets every day would be so dull without their voices in my head. Similarly the Projections Podcast, hosted by Sarah Kathryn Cleaver and Mary Wild. Both podcasts have given me a film education, and all I’ve had to do is walk around my neighborhood.

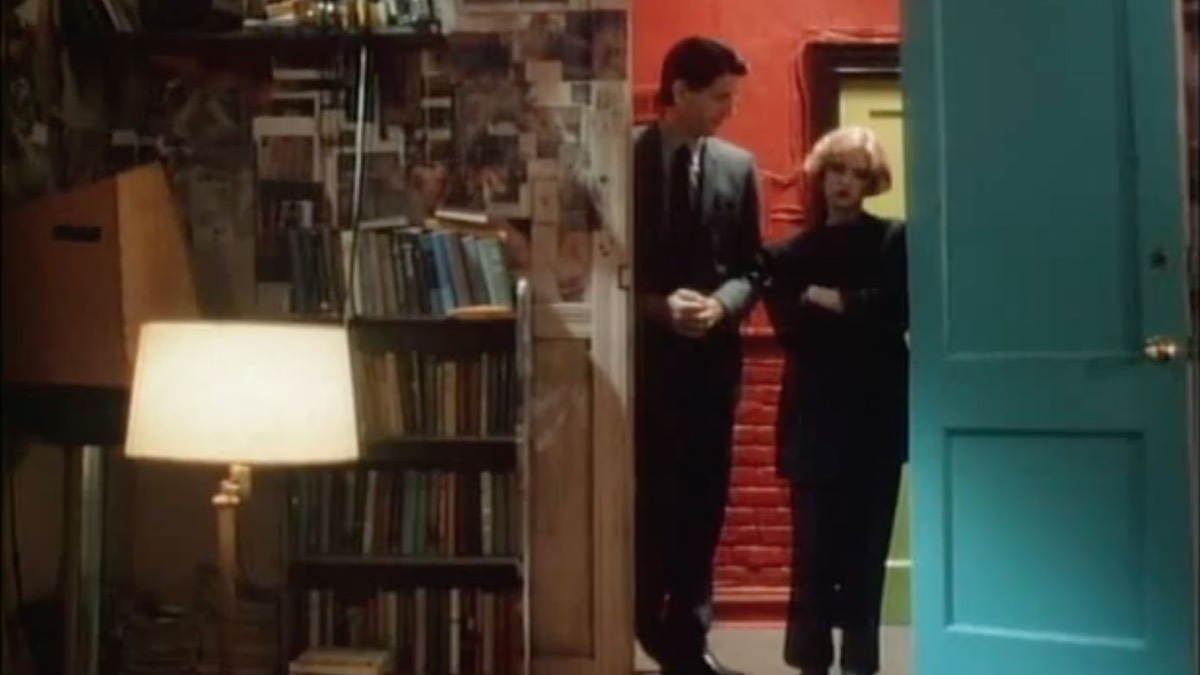

It was Elric Kane’s recommendation that led me to buy the spectacularly strange Heart of Midnight (1988) DVD (it is criminally unavailable streaming). Jennifer Jason Leigh, in one of her earliest roles, plays Carol, a young woman who inherits her dead uncle’s derelict sex club. It’s weird and icky, but Leigh is superb, it has bags of ideas, the club location (The Midnight) is inspired, and by switching between reality and dreams, it has some glorious surreal imagery. It’s a cult wonder.

Equilibrium is a novella by Tonino Guerra, first published in 1967, but republished in 2020 by Moist as the first in a ‘trilogy of alienation’. A graphic designer in Milan heads to a villa on the east coast of Italy to come up with ideas for a font for a kitchen company. The abstractions of his life serve to distance him from his feelings about the second world war concentration camp he survived, but he finds himself adrift and increasingly manic in the modern world. He is fearful and neurotic, creative and successful, but he knows his work is ultimately pointless. It’s like a Charlie Kaufman film on 10x speed, because at times each line is another decision or idea that distracts him, and the reader. It reminded me of Slaughterhouse 5. The nameless protagonist is looking for some sort of equilibrium, but the forces assailing him are too powerful, and he craves the repetition of his trauma. Perhaps he finds some peace in his art.

Staying with European writers, I had another go at The Art of the Novel, by Milan Kundera — a series of essays on what he is trying to do with his novels. It’s a tough book because Kundera loves philosophy and has a deep knowledge of literature. I do not (to both). Last time I attempted it I didn’t finish the first essay, but this time I got over halfway through the book. I’m with him on celebrating life’s complexity in novels and not going the easy route, but I write (and read) because I love stories, and I love characters, whereas he loves the ideas more. His characters are almost pure ciphers for the problems he is thinking through. That’s not my bag.

As if to prove my point, I also watched The Grinch (2018) and Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale (2010). Both show the shadows of the Christmas season, but where the Grinch is (very) cute and grumpy, the Rare Exports’s Santa Claus is a giant horned devil encased in ice, and his elves are naked old men who steal children in the night. I loved the gritty portrayal of the lives of Finnish reindeer hunters. It’s an antidote to the Coca-Cola Christmases it makes fun of.

And finally, to round this mammoth post off, De Palma (2015). It was fascinating, if a bit shallow, and is simply Brian De Palma telling the stories behind every film in his filmography. The interviewers edit their questions out, and show illustrative scenes from the films, so it’s De Palma’s voice for two hours. Fortunately he’s a charismatic, likeably forceful interviewee, and is not afraid to speak his mind, which gives the film spark, but the time flies by, so it’s a whistle-stop tour, which is a shame.

Films:

- Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale (2010), dir. Jalmari Helander;

- The Grinch (2018), dir. Scott Mosier, Yarrow Cheney

- Heart of Midnight (1988), dir. Matthew Chapman

- De Palma (2015), dir. Noah Baumbach, Jake Paltrow

Books:

- Equilibrium, by Tonino Guerra, Eric Mosbacher (Translator)

- The Art of the Novel, by Milan Kundera, Linda Asher (Translator)

Why do I write here?

I’ve written more posts on my blog in 2020 than ever before. It was tricky to start with — I had to find a new voice and get in a groove. As the year ends, and I begin to think about 2021, I find myself wondering, are they worth the time I put into them? I might get a few extra passersby from the links I post to Twitter, and so might sell a handful of books, but that isn’t why I write here. Why do I write here?

I’ve mostly written about films this year. Doing that has definitely deepened my experience of them. The act of writing makes me think more thoroughly. An essay starts with a title, a question, and I unconsciously have questions when I begin a film post. It’s only in writing this that I realise what they are. Why did I choose the film? What do I think about it? How does it make me feel? What did I really like about it? What memories does it evoke? How does it link to what is going on in my life right now? What didn’t work? I’m not interested in writing about how the film got made, where it fits in a director’s filmography, its box-office takings, or whether it got good reviews. I’m looking for a personal connection.

I don’t think of my posts as reviews because I’m looking for what is useful to me, and I’m biased towards my interests. Writing helps me pull out of other people’s creative work something of myself, from my unconscious — ideally for my own work-in-progress. That’s a high bar. Mostly I manage three or four paragraphs, with a brief synopsis, and a few things that struck me. I’m a devil for putting myself under unnecessary pressure, which helps get them written, but maybe keeps me in the experiential shallows. However, as in most things, something is better than nothing.

In the New Year I want to do things differently, write more about the connections between films and books, be more specific about what I’m looking for, and play with this blogging voice. It doesn’t have to be this way — this voice. There are many ways I can do this in 2021. That’s exciting.

London Gothic, Nicholas Royle

Author: Nicholas Royle

The protagonists of London Gothic are walkers, art lovers, film buffs and train nerds. They are loners, in the main, fascinated by urban spaces and routes between places. Through their eyes, we see the people who haunt the cafes, galleries and pubs of various parts of London, and we often go back to their houses, where we see their odd collections of things, or attempts at black magic. Sometimes they kill people, and sometimes we suspect they killed someone, but we’re not quite sure.

Some of these stories are published here for the first time, and others are older, with a couple reminding me strongly of his 2000 novel, Director’s Cut, which has London’s cinemas and underground stations at its heart. He can write straight prose like a dream, but he also plays with form, like in The Old Bakery, where a disgruntled editor makes increasingly bitter notes on a press release for an artisan bakery, and Artefact, with its six different points-of-view on a man’s innocent attempt to get his VHS tapes transferred to a digital format. If you like unsettling, dryly funny writing, then you can’t go wrong with this collection. It makes me miss London, even with its haunted houses and serial killers, especially now that the virus means I can’t go there.

As a final note, I want to point out that Nicholas Royle edited my novel, The Complex, and he recently published my short story, Signal, with Nightjar Press. The world of blurb, book bloggers and reviews can seem a little murky, and while I would be cynical about an author enthusing about his editor’s work, this post was written sincerely.

Exit Management, Naomi Booth

Author: Naomi Booth

The term ‘exit management’ is one Lauren’s HR consultancy uses as a euphemism for helping their clients to fire troublesome employees. Lauren is exceptional at it, and is highly valued by her monstrous boss, Mina, for her emotional control and ability to get the worst jobs done. Lauren meets Callum by colliding with him outside one of the expensive houses he is paid to look after. She thinks it is his, but it is actually owned by the terminally ill József, Cal’s favourite client and father figure.

Lauren, Cal and József’s stories intertwine. Each had challenging childhoods of different kinds. We see Lauren and Cal’s points-of-view in alternate chapters, with the old man’s voice coming from Cal’s love of hearing József talk. He worships József, who is happy to bring his parents’ memories back to life for Cal. We hear about Hungary’s role in the second world war, the fall of Budapest, and the fate of his mother, but he also educates Cal in classical music, paintings and culture. Cal is so close to József, that when Lauren thinks József is his father, he doesn’t correct her.

The prose style is brilliant, alternating between Lauren’s slowly fragmenting sense of control and Cal’s mixture of deep care for others and self-loathing. For all their front, both Lauren and Cal are from working class estates, and while József might be clear-eyed about what he needs from Cal, Cal and Lauren are driven by a mixture of ambition and more ambiguous unconscious desires. Anxiety is such a rich playground for playing with language. Where József seems to have found a way to live with his family’s history, Lauren and Cal’s family dramas play out in the present. Plenty can go wrong in the grey areas of what is assumed and not said.

November culture

It’s good to play around with your projects and try new things. I still suffer from a degree of imposter syndrome, and I probably always will. That’s partly a working class thing, but it’s also because I didn’t study literature or writing until I was well into my thirties. At this point in my life, nobody is going to give me a reading list. I have to create my own structures. I want to be more conscious of how the books I read, and the films I watch, play into my writing. That’s why I’m trying new things with this blog.

After watching so many films in October, I was desperate to read a book again. I chose The Glass Kingdom, by Lawrence Osborne. It follows the residents and workers in an expensive Bangkok apartment complex, after the arrival of Sarah, a serial con artist with a suitcase full of cash. The women Sarah falls in with are all escaping something and in different ways unengaged with the world round them. As the story unfolds, the city and its citizens impinge more and more into the lives of the privileged women. It made me think about how I approach point-of-view. Osborne breaks all the rules of holding one viewpoint at a time, and doing that makes it feel less personal and more like Bangkok is telling the story. His descriptions are brilliant. It’s bleak and impressive, but a little cold for my taste.

I decided to go all-in on Mubi in 2021 and bought a subscription. I started with Two Days, One Night, in which we meet Sarah, who works at a solar panel factory somewhere in France, and is suffering from depression. Her co-workers are forced to vote between keeping her on or having a substantial bonus. After finding out on a Saturday morning they voted for a bonus, the rest of the film follows her attempts over the weekend to convince each of her fifteen co-workers to change their minds. Everyone is on the poverty line except the factory boss, who doesn’t care about the fallout. The vote pits employees against each other. The interactions are sometimes brutal, sometimes empathic, but always understated. The film rewarded my patience.

In contrast, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse was a joyous experience from beginning to end. It’s fun, has emotional depth, and is easily one of my favourite films this year. Other films I watched in November, in descending order of enjoyment: Finding Vivian Maier (2013), Bruce Springsteen’s Letter to You (2020), Color Out Of Space (2019), Opera (1987), Eames: The Architect and the Painter (2011), Transamericana (2020).

Jigsaws

My mother loved to do jigsaws. She would stay up late, after every one else had gone to bed, and do them on the dining table, which is also where she would do the bookkeeping for whichever company she was working for at the time. When she died, I found all the lists and accounts she kept for the household budget, and I remembered how she showed me how to keep track of my spending when I went off to university. She was renowned for balancing complicated accounts to the penny with only a calculator, pen and pencil, even after computers could do it all much faster. That was the jigsaw energy. She always needed things to be right when it came to her work.

I see that tendency in myself. When I do a jigsaw, I can feel my mother with me, and that’s comforting. I can let life flow over and around me, and I’ll never know now whether she was able to do that, but when something feels important, and I set my mind to it, I need it to be done to the best of my ability.

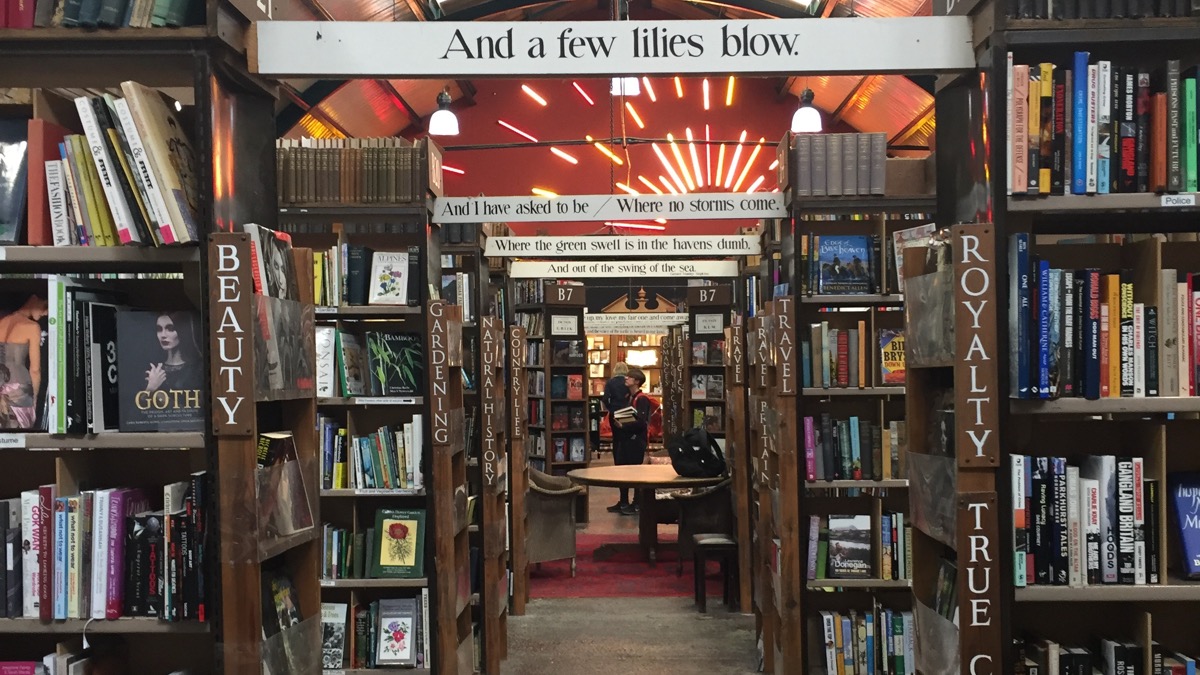

For Christmas last year I bought my daughter a jigsaw of a book shop. Facing a long November and December in another lockdown, I dug it out again, and bought a puzzle board to put it on, so I could push it under the sofa between sessions. (That didn’t work out, it turns out our sofas are all too low to the ground for the board to fit. It’s still useful.) As I’ve worked on it, painfully aware of the guilt I’m feeling about not working on my next novel, it’s become clear I fight my natural instincts. I make creativity more painful than it needs to be.

There are parallels with writing in the way I do jigsaws. I start by turning over all the pieces and looking for the edges. My mother taught me that. The edges provide a boundary. Then I look for the vivid, smaller sections, which are easier to find in the mass of pieces, and put them in roughly the right spots. At some point these sections connect to each other, or most thrillingly to the edges, and things speed up. By this point, my mind has spent enough time on the problem to begin to see connections before I consciously notice them. My fingers move to a piece without knowing why, and it fits somewhere unexpectedly. The whole assembles itself because I’m fully engaged, and the power of my pattern-matching mind, which I undoubtedly got from my mother, shines though.

Don’t get me wrong, that isn’t how I wrote my first book, and I’m not sharing my jigsaw-as-creative-writing metaphor because I know it’s right, but it might help me unlock my current work-in-progress, which also seems to be waiting for when I can sit at a cafe table again, where I’ve always written most of my words. The jigsaw energy and writing energy is surely also linked to the way I write software. It’s human to want to assemble patterns out of what seems like chaos. My problem-solving mind craves patterns. Anyway, that’s what I wanted to say about jigsaws.

Creativity 2.0(.21)

I’m in a fallow period, pottering around, looking for the next thing. I started a jigsaw, read a novel, watched the first half of Homecoming (Season 1, with Julia Roberts), listened to podcasts on my walks, and wrote in my notebook. Work was busy, and working from home I find it hard to switch off. I’m easily distracted. The US election sucked a lot of energy out of me. The news is everywhere now. Since finishing #31DaysOfHorror I’ve lost momentum in personal projects. That groove was a powerful source of creative energy.

Finally, though, I’m beginning to feel more centred. Within a couple of weeks, 2021 has gone from being the beginning of the end of things, to the beginning of something new — Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, a COVID-19 vaccine, the end of Dominic Cummings — these are all excellent for my mental health. The world is starting to feel safer.

I now know I can watch a film, make some notes about it, let it simmer in the back of my mind for a few days, then edit it into a decent piece of writing, and I can do that several times a week if necessary. That’s new. I’m not sure what those #31DaysOfHorror blog posts were. They felt like reviews, but I didn’t want to give an opinion on whether films were good, bad, or worth someone’s time. Instead, I tried to find what I liked about each film, then connected it with previous films or my own experiences. I felt obligated to provide a brief synopsis, perhaps because I always had the reader in mind, and they might not have seen the film. I wanted each post to make sense and stand alone.

A handful of people read them. That felt good. The one-film-a-day structure was a potent catalyst for making it a habit, as was posting a link to the post on Twitter. I was pretty wrung out from watching so many films in such a short period. I did love it, but after I’d finished, once I’d let myself decompress, it felt like a massive relief. However, I engaged more deeply with films knowing I had to write about them — that was the power of the challenge, and the public commitment that came with it.

I stopped watching films and writing blog posts completely in November. Drifting creatively is useful, but I’ve learned that without a project, eventually I lose sight of the coastline of my true interests and drift out to sea. I’d like to keep the bits that worked from #31DaysOfHorror, but make it less intense, more sustainable, and more aligned with my current goals.

Posting to my blog every day kept me accountable. That was my measure of progress. Looking back at those thirty-one posts I see what I achieved, and I feel proud of a good creative project. Having a page on my website pulling those posts together makes it feel coherent, just like seeing The Complex and Signal existing in the world does.

My next novel is plodding away in the background. I sit with it for up to an hour every morning. Some days I write a hundred words, occasionally I write none, but on other days I might write as much as five hundred. It’s intermittent and slow-going. Publishing short blog posts and posting them on Twitter — hell, just posting on Twitter and getting a few likes — gives me a feeling of accomplishment, and a dopamine rush writing a novel can’t compete with day to day.

A short story is a month’s work for me, and a novel is years of effort. This novel might never get published and only be read in three years time by one diehard fan willing to read an 80,000-word .docx file. I love you, man, but if the Time Wizard showed me his crystal ball, and that was how it was going to be, I’m not sure if I would go on. The hope of being published and having my work exist on its own terms in the world is a sustaining force. Without that hope, I’d like to think I would still write stories, because it serves some internal purpose, but honestly, I don’t know.

That’s what I’m competing with in my head. I don’t want my writing practice to feel leaden and dull. I’m writing good sentences, even though it is difficult work. Writing The Complex, I had the structure of a creative writing Masters to get a draft finished. Now I’m in the world, a published author, but with no agent, no contract, no support structures, working full-time at home in a completely different field, living through a pandemic, with one child in secondary school and another at a COVID-ridden university, trying to keep some momentum going.

There is transition energy afoot. It’s been a fuck of(f of) a year. I’m starting my annual process of looking back, so I can look forward. I’m lucky in all the ways that matter. Writing is hard — it has always been hard — but it still feels like the most important thing I can do with my spare time. I don’t write for the pleasure of writing, but it means a lot to me, and I manage to create space in my life to do it. For that I am thankful.

Over the next few weeks, as we come to the end of 2020, everything I’ve written about here will shake out. I can’t stay still for long, although I do try. The ideal I hold in my head of a slow, loving, meaningful life always seems just out of reach, but I do my best with what I have.

I wonder what next year will bring? I wonder how I can make my craft feel more fun? With those questions in mind, we enter a season of change.